अन्य देशों के विपरीत भारत में कास्ट-व्यवस्था को सामाजिक विशिष्टता के रूप में प्रस्तुत करने की एक अनोखी प्रवृत्ति रही है। जाहिर है, पश्चिमी दुनिया में व्याप्त सामाजिक उंच-नीच(अनुक्रम) और बहिष्कार के इतिहास पर पर्याप्त ध्यान नहीं दिया जाता है, न ही ब्रिटिश उपनिवेश के अधीन भारत में सामाजिक वर्गीकरण के अनोखे विकास की पूरी तरह से सराहना की जाती है।

रत की कास्ट-व्यवस्था और ‘छुआ-छूत’ बड़ी संख्या में सामाजिक विज्ञान शोधकर्ताओं, इतिहासकारों और यहां तक कि आधुनिक समय में आम जनता के लिए गहरी रुचि का विषय रहा है। भारत में व्याप्त कास्ट की धारणाओं ने गैर-भारतीयों के दिमाग में ऐसी गहरी जड़ें जमा ली हैं कि मुझे अक्सर पश्चिमी लोगों के साथ अनौपचारिक बातचीत के दौरान पूछा जाता है कि क्या मैं अगड़ी कास्ट की हूँ?

यह आश्चर्यजनक नहीं है, क्योंकि आज भी अमेरिका में ‘वर्ल्ड सिविलाइजेसन: ग्लोबल एक्सपीरियंस’ (एपी संस्करण) जैसे हाईस्कूल की पाठ्यपुस्तकों में ऐसे पूर्वाग्रहजनित वाक्यों को शामिल किया गया है: ” शायद, भारतीय कास्ट-व्यवस्था एक प्रकार का ऐसा सामाजिक संगठन है जो आधुनिक पश्चिमी समाज के सर्वाधिक महत्त्वपूर्ण सिद्धांतों, जिनपर समाज टिका है, का उल्लंघन करता है।”

आश्चर्यजनक रूप से, खुद भारतीयों ने ‘निम्न कास्ट और अस्पृश्यों के शोषण’ की इन सभी कहानियों को आत्मसात कर लिया है, और किंचित ही कभी इसकी वैधता पर प्रश्न उठाया है, न ही पश्चिमी दुनिया में व्याप्त ऐसी प्रथाओं के बारे में जानना चाहा है| क्या भारत में छोड़कर विश्व भर में वास्तव में कोई कास्ट-व्यवस्था नहीं थी? यूरोप के समृद्ध नागरिकों के शौचालय से मानव मल को खाली करने वाले लोगों के साथ कैसे व्यवहार किया जाता था? मानव-शवों और पशु-शवों को ठिकाना लगाने वाले लोगों के साथ कैसे व्यवहार किया जाता था? क्या ऐसे लोगों को अमीर लोगों के समकक्ष बैठने या अपनी बेटे-बेटियों की उनसे शादी करने का अधिकार था?

अधिकांश लोगों को यह जानकर आश्चर्य होगा कि 20 वीं शताब्दी तक यूरोपीय कास्ट-व्यवस्था के तहत, निचली कास्ट के लोगों का जीवन बहुत दयनीय था। डीफाइल्ड ट्रेड एंड सोशल आउटकास्ट- ऑनर एंड रिचुअल पॉल्यूसन में लेखक कैथी स्टीवर्ट ने 17 वीं शताब्दी के उन सामाजिक समूहों का वर्णन किया है जो “व्यापार की प्रकृति के कारण हीन” थे जैसे जल्लाद, चमार, कब्र खोदने वाले, चरवाहे, नाई-सर्जन, आटा चक्की वाले, लिनन-बुनकर, बो-गेल्डर, अभिनेता, शौचालय सफाईकर्मी, रात्रि-पहरेदार और न्यायिक कारिन्दा।

एम एस स्टीवर्ट इन व्यवसायों को नीच दृष्टि से देखने को रोमन साम्राज्य की देन मानते हैं। “रोमन साम्राज्य के दौरान ‘नीच’ व्यावसायिकों को ‘उच्च’ कुशल कारीगर समूहों और पुरे समाज के द्वारा जनित सामाजिक, आर्थिक, कानूनी और राजनीतिक भेदभाव के विभिन्न रूपों का सामना करना पड़ा| समय के साथ, ‘नीच’ लोगों को अधिकांश समूहों से बाहर कर दिया गया| सर्वाधिक अपमानित वर्गों जैसे जल्लादों और चर्म-कर्मियों को ‘उनएयरलिक्काइट’ (अपमान की एक अवधारणा) नामक प्रथा का शिकार होना पड़ा जिसमे उन्हें लगभग सभी सामान्य समाजिक समूहों से बहिष्कार का सामना करना पड़ा। जल्लादों और चर्म-कर्मियों को कोई भी कंकड़ फेंककर मार सकता था, उन्हें सार्वजनिक स्नान से बहिष्कार, सम्मानपूर्वक दफन करने से इनकार और महज शराब के हक़ से भी इनकार कर दिया जाता था जो उस समाज में आम लोगों को आसानी से उपलब्ध था। यह अपमान आने वाली कई पीढ़ियों को अपने पिता से मिले धरोहर के रूप में भी झेलना पड़ता था। हीनता में ‘छूत’ का माना जाना इस कुरीति की प्रमुख विशेषताओं में से एक है। हीन लोगों के साथ अनौपचारिक संपर्क में आकर या आचरण के कुछ अनुष्ठान नियमों का उल्लंघन करके सम्मानित नागरिक स्वयं को हीं महसूस करते थे। एक उच्च वर्ग के कारीगर के लिए अशुद्ध होना विनाशकारी होता था।एक समूह के जिन लोगों पर अशुद्ध होने का कलंक लगा होता था उन्हें एक प्रकार की सामाजिक मौत का सामना करना पड़ा। उन्हें अपने समाज से बाहर रखा जाता और उनसे उनके व्यवसाय करने का हक़, जो समूह की सदस्यता द्वारा मिलता था, भी छीन लिया जाता था ताकि वह अपनी आजीविका, सामाजिक और राजनीतिक पहचान दोनों खो दें। यहां तक कि व्यक्तिगत संपर्क के माध्यम से छूत का डर इतना खतरनाक होता था कि पड़ोसी और पास खड़े लोग के सामने व्यक्ति मर भी रहा हो तब भी कोई उसकी मदद नहीं करता था। एक नाटकीय उदाहरण एक जल्लाद की पत्नी का है जो 1680 के दशक में उत्तर जर्मन शहर हुसूम में प्रसव में मरने के लिए छोड़ दी गई, क्योंकि मिडवाइफ ने जल्लाद के घर में घुसने से भी इंकार कर दिया था। ”

सम्पूर्ण इतिहास में, कचरे और मल साफ करने का काम करने वालों को कभी भी सम्मान की नजर से नहीं देखा गया। 20 वीं शताब्दी के उत्तरार्ध तक, यूरोप में मानव माल-मूत्र को पखाने के गड्ढे से हाथ से ही साफ किया जाता था। ‘नीच कर्म’ करने वाले निम्न वर्ग के यूरोपीय लोगों को अंग्रेजी में ‘गोंगफर्मर्स’ (फ्रेंच) या ‘गोंग फार्मर्स’ कहा जाता था। क्या आपको लगता है उनका समुचित सम्मान किया जाता था और उन्हें समाज के उच्च वर्ग के साथ स्वतंत्र रूप से घुलने-मिलने की इजाजत थी?

इंग्लैंड के गोंग फार्मर्स को केवल रात में काम करने की इजाजत थी, इसलिए उन्हें ‘नाइटमेन’ भी कहा जाता था। वे उच्च वर्ग के लोगों के घरों में रात को आते थे, पाखाने के गड्ढे को खाली करते थे और उसे शहर की सीमा के बाहर छोड़ आते थे। उन्हें शहर के बाहर कुछ क्षेत्रों में ही रहने की इजाजत थी और दिन के दौरान वे शहर में प्रवेश नहीं कर सकते थे। इस नियम को तोड़ने पर उन्हें गंभीर दंड मिलता था। कमोड के प्रयोग में आने के बाद भी,लंबे समय तक, मल-मूत्र पखाने के गड्ढों में ही बहता था और इसे ‘नाइटमेन’ द्वारा साफ करने की आवश्यकता पड़ती थी।

दुनियाभर में, जब तक सीवेज और मल के परिवहन और प्रबंधन की आधुनिक व्यवस्था अस्तित्व में नहीं आई, तब तक इन श्रमिकों को समाज से बहिष्कृत ही किया जाता था।आधुनिक शहर जब तक लाखों प्रवासियों, जो विविधता और विषमता को बढ़ाने में भी मदद करते थे, के आ जाने से प्रदूषित नहीं हो गए, समुदाय काफी बंद प्रकार के और दूसरों का बहिष्कार करने वाले होते थे।

दिलचस्प बात यह है कि अंग्रेजी शब्द ‘कास्ट’ पोर्तगीज शब्द ‘कस्टा’ से लिया गया है। इसका इस्तेमाल उन स्पेनिश अभिजात वर्गों द्वारा किया जाता था जिन्होंने विजय प्राप्त क्षेत्रों पर शासन किया था। ‘सिस्टेमा डी कास्ट’ या ‘सोसाइडा डी कास्टों’ जैसे शब्दों का इस्तेमाल, 17 वीं और 18 वीं सदी में,स्पेनिश-नियंत्रित अमेरिका और फिलीपींस में मिश्रित प्रजाति वाले लोगों के वर्णन करने के लिए उपयोग होता था। ‘कास्टा’ व्यवस्था ने जन्म, रंग और प्रजाति के आधार पर लोगों को वर्गीकृत किया। एक व्यक्ति जितना अधिक गोरा होता था, उसको उतना अधिक विशेषाधिकार प्राप्त था और कर का बोझ भी कम होता था। कास्टा, ईसाई स्पेन में विकसित रक्त की शुद्धता के विचार का विस्तार था जो बिना यहूदी या मुस्लिम विरासत से कलंकित लोगों के बारे में सूचित करता था। स्पैनिश आक्रमण के वक्त जब पुराने धर्म वापस अपनाने के संदेह पर हजारों परिवर्तित यहूदी और मुस्लिम (यूरोपीय, निम्न वर्ग) को मार दिया गया था तब तक तो ऐसी अवधारणाओं ने काफी गहरी जड़ें जमा ली थी।

एडवर्ड अलसवर्थ रॉस ( प्रिंसिपल्स ऑफ सोशियोलॉजी, 1920) यूरोप की कठोर और सख्त ‘कास्टा’ व्यवस्था का एक विस्तृत विवरण देते हैं और कहते हैं कि यह यूरोपीय समाज के भीतर शक्तियों की देन था। वह कहते है:

“रोमन साम्राज्य पुरुषों को अपने पिता के व्यवसाय का ही पालन करने और अन्य व्यवसाय या जीवन-यापन के तरीकों के बीच एक मुक्त परिसंचरण को रोकने को मजबूर कर रही थी। वह व्यक्ति जिसने अफ्रीका के अनाज को ओस्टिया के सार्वजनिक भंडार तक पहुचाया, मजदूर- जिन्होंने इसे वितरण के लिए ब्रेड बनाया, कसाई – जिसने सामनियम, लुकेनिया, ब्रूटीअम से सुअर लाया, शराब विक्रेता, तेल विक्रेता, सार्वजनिक स्नानघर की भट्टियों में कोयला डालने वाला, पीढ़ी दर पीढ़ी उसी काम को करने को बाध्य थे… इससे बचने का हर दरवाजा बंद कर दिया गया था … लोगों को अपने समूह से इतर शादी करने की इजाजत नहीं थी …किसी प्रकार शाही फरमान हासिल करने के बाद भी नहीं, यहां तक कि शक्तिशाली चर्च भी इस दासता के बंधन को नहीं तोड़ सकते थे।”

भारतीय ‘कास्ट व्यवस्था’ ब्रिटिश उपनिवेशवादियों द्वारा लगाया गया एक पहचान था, पर इस पहचान ने समाजिक विभाजन का सही ढंग से प्रतिनिधित्व नहीं किया। वेदों में, रक्त की शुद्धता , जो यूरोप की कास्ट-व्यवस्था की विशेषता थी, की कोई अवधारणा नहीं थी। दूसरी तरफ, कार्यों और व्यक्तिगत गुणों के आधार पर व्यक्ति का वर्ण निर्धारित करने की अवधारणा थी। भारतीय शब्द “जाति”, जो कि समाज के व्यावसायिक विभाजन को नाई, चमार, मवेशी-पालक, लोहार, धातु श्रमिकों और अन्य व्यापारों के रूप में इंगित करता था, सिर्फ भारत में ही एक अवधारणा नहीं थी (भले ही ‘कारीगरों के समूह’ की अवधारणा का जन्म भारत में ही हुआ था)। दुनिया में बसने वाले हर समाज में, बेटों ने परंपरागत रूप से अपने पिता के व्यवसाय को ही अपनाया। बढई के पुत्र बढई बने। बुनकरों के पुत्र बुनकर बने। ऐसा होना स्वाभाविक भी लगता है क्योंकि बच्चे अपने पिता के व्यापार से अच्छी तरह से परिचित होते थे, और अपने व्यापार की अनोखी विशेषताओं को सम्हालकर गुप्त रख सकते थे।

भारत में, जातियों को विभाजित करने वाली रेखाएं शुरू में धुंधली थीं और लोगों के कुल से हटकर व्यवसाय अपनाने के कई उदहारण भी मिलते हैं| निचली जातियों के संत रवीदास, चोखमेला और कनकदास ने लोगों का सम्मान अर्जित किया और उन्हें ब्राह्मण संतों से कम नहीं माना जाता था। मराठा पेशवा ब्राह्मण थे जो बाद में क्षत्रिय बन गए थे। मराठा राजा शिवाजी जिन्होंने कई साम्राज्यों पर अपनी जीत के बाद उदार ब्राह्मणों के समर्थन से खुद को क्षत्रिय घोषित कर दिया था, को शुरुआत में निचली जाति का माना जाता था| प्रसिद्ध समाजशास्त्री एमएन श्रीनिवास कहते हैं:

“यहां ध्यान देने वाली बात यह है कि एक क्षेत्र में असंख्य छोटी जातियों का समाज में स्पष्ट और स्थायी अधिक्रम नहीं रहता। अधिक्रम का परिवर्तनशील होना ही वास्तविक समाज को काल्पनिक समाज से अलग करता है। वर्ण-व्यवस्था जाति व्यवस्था की वास्तविकताओं की गलत व्याख्या का कारण रहा है। हाल के क्षेत्र-शोध से यह बात सामने आई है कि अधिक्रम में जाति की स्थिति एक गांव से दूसरे गांव में भिन्न हो सकती है। अलग-अलग जगहों में सामजिक अधिक्रम परिवर्तनशील होता है और जातियां समय के साथ बदलती रहती हैं| इतना ही नहीं, सामाजिक ओहदा कुछ हद तक महज स्थानीय भी होता है।”

यह भी ध्यान दिया जाना चाहिए कि यूरोप के विपरीत, भारत में उच्च और निम्न वर्ग का विभाजन कभी भी आर्थिक विषमता के कारण नहीं हुई। ब्राह्मण परंपरागत रूप से सबसे गरीब, प्रायः याचक ही होते थे। वैश्य और शूद्र व्यापारी प्रायः अमीर होते थे और अक्सर ब्राह्मणों की सेवा लेते थे। आमतौर पर, भूमि क्षत्रिय, वैश्य और शुद्रों के स्वामित्व में थी। प्रसिद्ध गणितज्ञ आर्यभट्ट स्वयं एक गैर-ब्राह्मण थे और फिर भी उनके अधीन नंबूदरी ब्राह्मण शिक्षा ग्रहण करते थे। आज भी, सैकड़ों ब्राह्मण जाति के लोग भारत में शौचालयों की सफाई में कार्यरत हैं, जबकि किसी को भी अमेरिका में एक स्वेत व्यक्ति द्वारा एक कचरा ट्रक चलाना हैरानी की बात लगेगी।

इतिहासकार धर्मपाल ने 18 वीं शताब्दी में स्वदेसी शिक्षा प्रणाली पर अपनी किताब ‘द ब्यूटीफुल ट्री’ में लिखा है कि मद्रास, पंजाब और बंगाल प्रेसीडेंसी में किये गए ब्रिटिश सर्वेक्षणों ने भारत में बच्चों के विद्यालयों में व्यापक नामांकन का खुलासा किया। लगभग हर गांव में एक विद्यालय था। कई विद्यालयों में शूद्र बच्चे ब्राह्मण बच्चों से अधिक संख्या में थे। इन स्कूलों को धीरे-धीरे बंद कर दिया गया क्योंकि ब्रिटिश शासन में गरीबी व्यापक हो गई थी और ग्रामीण नौकरियों की तलाश में शहरों को चले गए।

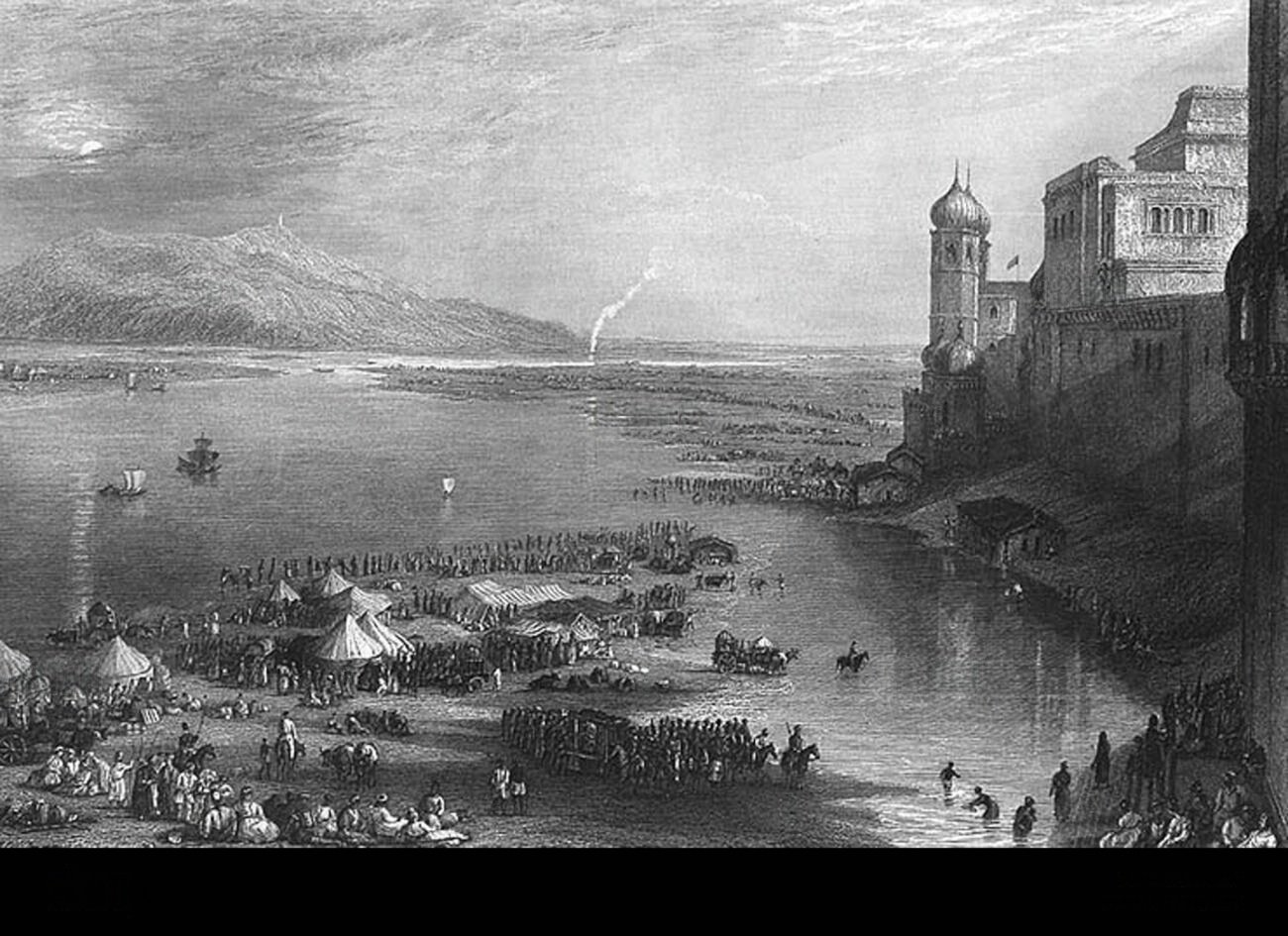

स्पेनिश औपनिवेशिक कला – मेक्सिको की कास्टा प्रणाली।

विदेशी आक्रमणों और “फूट डालो शासन करो ” की ब्रिटिश नीति जैसे विभिन्न कारकों के कारण जाति विभाजन अधिक कठोर हो गया। जब तक अंग्रेजों ने 1881 से विभिन्न उपनामों को विभिन्न जातियों में सूचीबद्ध करने के लिए व्यापक जनगणना नहीं किया, तब तक अधिकांश भारतीय जातियों के अधिक्रम से अवगत नहीं थे। आम तौर पर, कुछ परिवार के नाम एक गांव में एक विशेष जाति से जुड़े थे और दूसरे गांव में एक अलग जाति के साथ। अचानक, जनगणना के कारण जातीय विभाजन की रेखा प्रगाढ़ हो गयी। अंग्रेजों द्वारा जातीय पहचान पर इसलिए इतना जोर दिया ताकि भारतीय समाज जातियों में बटे रहें और अंग्रेजों के खिलाफ एकजुट न हो सकें| इसके कारण जातियों में आपस में गहरे विवाद पैदा हो गए| ब्रिटिशों द्वारा कई अनुसूचित जातियों और जनजातियों को आपराधिक श्रेणियों में रखने से भी जातीय रेखाएं प्रगाढ़ हो गयीं जो स्वतंत्र भारत के लिए विनाशकारी परिणाम लेकर आई। विडम्बना यह है कि वर्ग और कास्ट में विश्वास रखने वाले ब्रिटिश ने भारतीय जातियों को सूचीबद्ध किया, उन्होंने अंग्रेजी महिलाओं को भारतीय पुरुषों से शादी करने की इजाजत नहीं दी, जबकि भारतीय महिलाओं को अंग्रेजों द्वारा रखैल की तरह अपनाने में भी उन्हें कोई आपत्ति नहीं थी।

यह याद रखना चाहिए कि भारत की व्यवसाय आधारित जाति प्रणाली की ढीली संरचना को बदनाम और सख्त करना ईसाई मिशनरियों की रणनीति का हिस्सा था। गवर्नर जनरल जॉन शोर के ईसाई धर्म के क्लैफम संप्रदाय के सदस्य बनने के बाद भारत में मिशनरी गतिविधि में काफी वृद्धि हुई। अपने “अंधविश्वास वाले धर्म” के कारण हिंदुओं को “मानव जाति का सबसे पिछड़ा और असभ्य लोग” घोषित किया गया था। विलियम विल्बरफोर्स, जो दास-विरोध के प्रणेता माने जाते थे और क्लैफम सेक्ट के सदस्य भी थे, ने 1813 ई. में हाउस ऑफ कॉमन्स में घोषित किया कि हिंदुओं को अपने धर्म से मुक्त करना हर ईसाई का पवित्र कर्तव्य है, वैसे ही जैसे अफ्रीका को गुलामी से मुक्त कराना।

दुनिया में कोई भी देश असमानताओं से मुक्त नहीं है। ऐसा होना अधिक पैसे और अधिक शक्ति के लिए निरंतर मानव प्रयास के द्वारा भी सुनिश्चित होता है। भेदभाव व्यापक रूप से फैला हुआ है और गैर-ईसाई, गैर-मुस्लिम, काले, समलैंगिक, महिलाएं, एड्स रोगी या कुष्ठरोगी इसके प्रमुख शिकार रहे हैं। पश्चिमी समाजों में ऐतिहासिक रूप से प्रचलित नस्लवाद जो आज भी विभिन्न रूपों में जारी है, यह भी घातक कास्ट व्यवस्था का एक रूप ही है। होलोकॉस्ट के लिए नाज़ीवाद और यहूदी-विरोध को दोषी ठहराया जाता है, लेकिन शायद ही लोगों ने इसे कास्ट-व्यवस्था के बुरे परिणाम के रूप में देखा है| यहां तक कि संयुक्त राष्ट्र सुरक्षा परिषद में केवल पांच स्थायी सदस्यों का होना भी कास्ट-व्यवस्था है, जिनके पास वीटो शक्तियां हैं। आइवी लीग विश्वविद्यालयों के स्नातक और विशिष्ट क्लब के सदस्य भी अपने स्वयं के कास्ट विशेषाधिकारों का फायदा उठाते हैं।

यह तर्क दिया जा सकता है कि भारत ने ऐतिहासिक रूप से वंचित जातियों की सहायता के लिए “आरक्षण” नामक दुनिया की सबसे बड़ी सकारात्मक योजना को लागू किया है। सरकारी स्कूलों और कॉलेजों में आरक्षित स्लॉट के साथ, सरकारी सेवाओं में पदों और चुनावी निर्वाचन क्षेत्रों में आरक्षित सीटों के साथ समावेशी होने का एक बड़ा प्रयास किया गया है। भले ही इन प्रयासों के अच्छे परिणाम मिले हों या नतीजतन “विरोधी कास्ट व्यवस्था” ने जन्म ले लिया हो, यह जांच का विषय है।

भारत में कास्ट-पहचान का आधुनिक वर्गीकरण और इसकी विचित्र अभिव्यक्ति ब्रिटिश और भारतीय सरकारों की संस्थागत नीतियों का बुरा परिणाम है जिसमे मार्क्सवादियों और अल्पसंख्यकों, साथ ही साथ गरीबी और विकास के अवसरों की कमी का बड़ा योगदान है। कास्ट-पहचान हिंदू परंपराओं में समाज के मूल वर्गीकरण की किसी कल्पना की विकृति की देन नहीं है।

यह सबसे उपयुक्त समय है कि दुनिया और स्वयं भारतीयों को भारत को कास्ट-व्यवस्था के चश्मे से देखना बंद कर देना चाहिए और दुनिया की हर हिस्से में कास्ट-व्यवस्था की शुरुआत के साथ-साथ सामाजिक-आर्थिक ओहदों को समझने का प्रयास करना चाहिए। इतने लंबे समय तक पश्चिमी शोधकर्ताओं के सामाजिक और मानव विज्ञान अध्ययनों का विषय रहने के कारण भारतीयों ने भी यह मानना शुरू कर दिया है कि प्रयोगशाला में नमूने की तरह, उनकी जगह भी माइक्रोस्कोप के नीचे है। यह लेंस को उलटे करने का समय है। भारत के बाहर एक पूरी दुनिया भारतीय परिप्रेक्ष्य से जांचे जाने और समझे जाने की प्रतीक्षा कर रही है।

The article has been translated from English into Hindi by Satyam

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness,suitability,or validity of any information in this article.

Events2 years ago

Events2 years ago

Videos3 years ago

Videos3 years ago

Events11 months ago

Events11 months ago

Videos11 years ago

Videos11 years ago

Events10 months ago

Events10 months ago