articles

What Hindus can learn from Batra vs. Doniger

Published

11 years agoon

By

ihar

Author: Dr. Jayakumar Srinivasan

Press Release: http://centreright.in/2014/03/what-hindus-can-learn-from-batra-vs-doniger-2/#.VTHsmNzBXlY

Contents:

- Introduction

- Vilification of Hindus and Hinduism

- Doniger’s Book, The Hindu Experience and Wendy’s Children

- Psychoanalysis and its Application to Hindu Figures

- Dialog with Purported Scholars of Hinduism

- Asymmetry and Labeling in Reporting and Discourse

- Calling Out the Labelers

- “Reductio ad Hindutva”

- “Reductio ad Taliban”

- “Donigeration”

- Conclusion

Introduction

Recently, after four years of engagement, Penguin agreed to an out-of-court settlement to voluntarily withdraw and pulp all copies in India of the book The Hindus: An Alternative History. Wendy Doniger, Distinguished Professor of History of Religions in the Divinity School of University of Chicago, is the author of the book.

Wendy Doniger is not new to Hindus. Around 2002, critically acclaimed researcher, writer and speaker, Rajiv Malhotra, reported his encounters and engagements with Religions in South Asia unit of the American Academy of Religion, where he identified Doniger as “undoubtedly the most powerful person in academic Hindu studies”. He exposed the disturbing syndrome of eroticization and denigration of Hindu traditions and practices.

Many have critiqued Wendy Doniger’s book. In this article, while referring to such works, I cover deliberate vilification of Hindus and Hinduism, asymmetry in reporting and discourse, application of unproven psychoanalysis and provide much needed labels to label the labellers.

Vilification of Hindus and Hinduism Abounds

Cases of disrespecting or outright vilification of Hindu icons and traditions have increased in the last decade. In India, the venerated H. H. Jayendra Saraswati Swamigal, Acharya of a 2000+ year old Kanchi Mutt, was arrested in a callous and disrespectful manner by the Tamil Nadu Government in 2004. Hindus felt vulnerable and confused. The mainstream Indian media, which blatantly disrespects the Hindu majority, was the first to act as the jury. Just a few months ago, the sham case was dismissed and the Acharya was acquitted. However, due to the muted coverage of the acquittal, the negative perception predominates in the public. Such disrespectful treatment of religious leaders is not imaginable in the US, as demonstrated by the treatment of proven cases of pedophilia in the Catholic Church. The Indian episode is equivalent to arresting the Pope on trumped up charges.

Recently, the Tamil Nadu government made an attempt to control the iconic Chidambaram temple. The Archaeological Survey of India quietly renamed the Shankaracharya Hill in the Kashmir Valley to Takht-e-Suleiman. Just a few months ago, fatwas were issued in the sacred town of Rameswaram that bars non-Muslims from entering Muslim-majority villages! Outrages such as these are rarely covered by mainstream media and are reported only by independent Hindu watchdogs. Examples such as these are numerous.

In the US High School History textbooks, portrayals of Hindus as monkey and cow worshippers, bride burners, and given to caste-based oppression abound in what Rajiv Malhotra has termed the Caste, Cows and Curry syndrome.

Doniger’s Book, The Hindu Experience and Wendy’s Children

In page 3 of the preface of The Hindus, the Hindu encounters a shrill message: Doniger indicates that she is presenting “a narrative of religion… as linga (an emblem of Lord Shiva often representing his erect phallus) as set in a yoni (the symbol of Shiva’s consort, or female sexual organ)…”. (section in parenthesis is part of her writing). This is the forerunner of things to come in her book.

Kaalidaasa, one of the greatest poets humanity has known, dedicated his classic Abhijnaana Shaakuntalam, to Shiva and Parvati, using a metaphor that the two are as inseparable as a word and its meaning in the famously known ‘vaagarthaaviva‘. In the Hindu tradition, it is customary to begin a class, program, or a book with a dedication to the ever-present Ishwara, such as Shiva, Vishnu, Saraswati or one’s Guru. I grew up as a Hindu, listened to many erudite Swamis on the spiritual, philosophical and practical essences of Hinduism, studied some Hindu texts, practiced Vedic rituals, spent all night worshipping Shiva during Shivaraatri, taught children the tenets and practices of Hinduism, and coordinated group-study of the Bhagavad Gitaa.

The word “linga” in the religious and spiritual context means “lingyate anena” or “that which is indicated by”. The oval shape has no beginning or end, signifying Brahman, that which is the essence of the entire world, that which always was, is and always will be, that which is all pervasive and indestructible. Brahman is that which cannot be categorically pointed to as an object of our sense-perception or inference, hence Shiva is often symbolically portrayed as “teaching in silence”. We grew up chanting Lingaashtakam (eight verses on Shiva in the form of Linga) that praises Shiva as the one who is worshipped as the liberator of the sorrows of life.

The western interpretation of the Shiv Linga as a phallic symbol is not the way the Hindus look at the Linga, as also pointed out by Prof. Balagangadhara in the book Invading The Sacred. In such circumstances, whose interpretation should have primacy, the Western or that of hundreds of millions of Hindus?

The book is littered with factual inaccuracies, blatant denigration, and racism. A Chapter wise review of the book, in particular, covering over 600 occurrences of factual errors, trivializations, and eroticization, has been meticulously developed by Vishal Agarwal, and partially by Chitra Raman. As an example from the book to quote: “If the motto of Watergate was Follow the money, the motto of the history of Hinduism could well be Follow the monkey or, more often Follow the horse.”, or “Dasharatha’s son is certainly lustful… when Lakshmana learns that Rama has been exiled, he says, The king is perverse, old, and addicted to sex, driven by lust”. Hindu Deities are presented as lustful, Hindu Saints are falsely alleged to have indulged in sexual orgies, or to have ‘taken actions against Muslims’, Hindu worshippers are compared to cheating boyfriends, intoxication is a central theme of the Vedas and Hindu scriptures are presented as a litany of tales of faithful women forsaken by their ungrateful husbands.

Prof. Madan Lal Goel of University of West Florida caught Prof. Doinger red-handed: “After building a caricature, she laments that fundamentalist Hindus … are destroying the pluralistic, tolerant Hindu tradition. But, why save such a vile, violent religion …?” Given the extreme nature of the writing, the burden is on her supporters to say how they are not siding with her in inaccurate characterization and intentional denigration of Hinduism.

In the book Kali’s Child, Jeffrey Kripal, Wendy Doniger’s protege, paints Ramakrishna Paramahamsa as a pedophile and Swami Vivekananda as a homosexual. In his book Ganesa, Paul Courtright, another student of Wendy Doniger, caricatured Ganesha with a trunk that is likened to a limp phallus and as one who is attracted to his mother Parvati. Even more egregiously, Courtright claimed that the Devi Bhaagavata Puraana records an incestuous rape by Daksha of his own daughter, the Goddess Sati. Doniger and her children accomplish such feats by filtering all the richness and complexity of Hinduism through a single perspective of a Freudian psycho-analytical approach applied to the exclusion of the others. In accomplishing the feat, Doniger and Wendy’s children take generous “scholarly” liberties in extrapolating the texts that they analyze with the academic license of psychoanalysis.

Psychoanalysis and its Application to Hindu Figures

Far from burning books or issuing fatwas, Hindus have undertaken a serious study of such “scholarship”. Rajiv Malhotra’s Infinity Foundation systematically present a critique of American Studies on Hinduism, in the book Invading The Sacred. Leading players, asymmetry of power between Euro-centric Academics and its critics, debates and exchanges, and the “science” of psychoanalysis are discussed.

Hindus must become familiar with the topic of psychoanalysis because Hindus are the subject of this less-known theory. Psychoanalysis posits that human attitude and thought are largely influenced by irrational unconscious drives. Conflicts between the conscious and unconscious results in states of neurosis, anxiety, and depression. Freedom from the unconscious material is obtained by bringing that material to the conscious through guidance.

Freudian psychology is far from an established science. It is not an evidence-based science. Karl Popper, who is famous for introducing the concept of falsifiability to demarcate between science and non-science, is famously known for viewing Freudian psychoanalysis as a pseudo science. Popper said that psychoanalysis was simply non-testable, irrefutable. There was no conceivable human behaviour which would contradict it. [Karl Popper, Conjectures and Refutations, p. 37. ] Or, as my mentor told me in my first job “If the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.” – so I have the solution to all problems.

In Freudian psychoanalysis, schizophrenia and depression are not brain disorders, but narcissistic disorders. Autism and other brain disorders are not brain problems but mothering problems. These illnesses do not require pharmacological or behavioral treatment. They require only “talk” therapy.

What has the application of Freudian psychoanalysis done to Hinduism?

In Invading The Sacred, Alan Roland, an ex-President of the National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis, explains the uses and misuses of this practice where “all … interpretations remain speculative”. Applied to Indian Swamis, it has reduced spiritual experiences to regressions into infancy, homoerotic phenomena, and psychopathological or defensive motivations. Observing an essential difference in the constituted individual – The Western individualized self vs. the Indian familial-communal self – Roland questions the applicability of Freudian analysis to Indians, leave alone spiritually accomplished Swamis. Roland views “attempts to link spiritual experience with various developmental stages as all being highly reductionistic”. Scholars “do not take sufficiently into account the existential nature of spiritual experience”. I feel this is an understatement. It is like a teenager observing that research (performed by Professors in University) is motivated by a sense of lack of self-worth.

Sudhir Kakar, an expert psychologist, observes in psychoanalysis the treatment of Indian culture and Indians as “patients”, a lack of respect and objectivity for the patient, and a disdain for mysticism.

What possible benefit can be obtained by analyzing, say Newton, to conclude (hypothetically) that his intellectual pursuit was a result of intense taunting and abuse he suffered in the family as a child? On the contrary, this gets into invasion of privacy and denial of tradition and knowledge. These so called scholars are outright disingenuous in selectively applying psychoanalysis to established Hindu figures. Malhotra observes that “Freud had ruled out …applying his methods either posthumously … or via native informants … not directly engaged by the psychoanalyst.” This reveals to us the troubled minds of these ‘scholars’, rather than the minds of Shiva, Ganesha or Ramakrishna. It seems to me that it is Doniger and her cohorts who need immediate psychological help, for which we seek Bhagavan Ganesha’s help!

The Hindu tradition allows us to recognize spiritually advanced individuals, called Swamis. For Hindus, our Swamis, who are our teachers, also serve as our personal counsellors and family guides. A Hindu, however accomplished professionally, can still be a spiritual child. I am reminded of the story when a professional went to a revered Swami and introduced himself as a ‘very successful marriage counsellor’. Upon being asked what brought him there, he said “My marriage is on the rocks!”

Alan Roland shares his experiences of applying psychoanalysis practice with several individuals who took up spiritual practice. Some of them were in failed marriages and wanted to escape family distress. He helped them see their motivations which in turn enabled them to lead more useful lives. In fact, the Swamis in the ashram where I study are routinely sought out for guidance on personal emotional challenges. Within seconds, they can spot personal pain underneath a spiritual interest. Teaching and counselling go hand-in-hand. This is why the tradition holds the first contact with a Swami as a defining moment in the life of a Hindu. Any system is prone to abuse and the tradition has its in-built way of weeding out charlatans.

Roland questions whether spiritual aspirations, practices, and experiences essentialize into regression, and criticizes Doniger’s school of universalizing Freudian techniques and developing wild theories of Indian culture. Roland observes that “If anything, clinical experience indicates that spiritual practices and experiences are a strong counterpoint to regression and childhood merger experiences with the mother and with the Hindu extended family”. The authors of the book Invading the Sacred analyze the scholarship of Wendy Doniger, Jeffrey Kripal, Sarah Caldwell, and Paul Courtright and ask the troubling question of whether their own personal psychosexual traumas are projected on to other cultures. Malhotra challenged Doniger at the 2000 AAR conference if she should be psychoanalyzed, and observes that Kripal’s need to distance himself from his half Roma/Hindu lineage through his father (and become 100% white) has manifested fully in his work.

Therefore, I view the process of psychoanalysing Hindu spiritual icons and giants by ‘scholars’ under the banner of ‘Hinduism studies’ as an underhanded way to vilify Hinduism.

Dialog with Purported Scholars of Hinduism

As much as Wendy and her children take liberties with Hindu texts, they do not evince similar openness in participating in discussions of their works. It is not that Hindu intellectuals did not try to establish a dialog with Doniger. After The Hindus was published, several Hindu scholars attempted to engage with Prof. Doniger. At the Association of Asian Studies annual conference in 2011, Prof. Madan Lal Goel of University of Florida organized a panel to discuss Prof. Doniger’s book. Prof. T. R. N. Rao, Professor Emeritus at Louisiana State University and Prof. Bharat Gupt of Delhi University were other round-table panelists. Doniger was invited several times by these individuals but declined to participate. Kripal likewise has not responded to Swami Tyagananda’s response to “Kali’s Child”. Says Arvind Sharma, Birks Professor of Comparitive Religion at McGill: “Such perceived indifference to an obviously credible critic was noticed by the Hindu community, … [who] took it upon themselves to explore the matter further.” “Nor is the cause of civilized intellectual discourse advanced if they decline to respond to informed critiques simply because the critics do not happen to be academics. It tempts the critics to conclude that the emperors have no clothes.”

Prof. Jeffery Long, chairman of the department of religious studies at Elizabethtown College, has voiced concerns about the consequences of such misinformation: “How many children will grow up believing Hinduism is a ‘filthy’ religion, or that Hindus worship the devil? When they grow up, how will such children treat their Hindu co-workers and neighbors? Will they give them the respect due to a fellow citizen and human being?”

Through a series of three articles, Paul Courtright was engaged in a debate in LittleIndia.com where Paul Courtright conceded that his interpretation of incestuous rape was unwarranted: “I’m not sure I would say explicitly, ‘Daksa raped Sati. Paul Courtright then adds: “I think the storytellers are trying to tell us something by not telling us everything. The project of interpretation is to try to get at not only what is said, but what is not said. Naming these unconscious desires is, of course, the project of psychoanalysis.” Little India’s independent analysis of the two passages based on the Puranas in Courtright’s book does lead to the conclusion that one of the claims is clearly erroneous, which he acknowledges, and the second is strained at best and unsupported by any of the many other versions of the story in the Puranas. Arvind Sharma observes that a “methodologically sophisticated slander of Hinduism was fast becoming an American academic pastime.”

Richard Crasta, knows very well the enormous barriers Indian writers face in getting their original work (especially those which challenge the Western establishment) published in India. In his satirical and riveting book Impressing the Whites, The New International Slavery (2000), he explains why nothing short of connections in the British Embassy may be needed to appear in the radar of powerful publishing houses in India. On the contrary, western authors can publish with ease in brown country, especially if it is derogatory about browns! The book publishing cartel in India seems to be controlled by the Brits.

Monika Arora is the legal counsel for Batra’s Shiksha Bachao Andolan Committee (SBAC, literally, Committee of the Movement for the Protection of Education). As for worries that this spoke poorly of India’s commitment to the freedom of expression, Monika Arora counters it with the argument that “freedom of expression does not mean freedom of defamation”. Many legal jurisdictions (including in the US) have adopted the substantial-truth doctrine which allows for restricting freedom of expression from overstepping onto defamation grounds. “Doniger has a history of defaming Hindus,” says Arora, “and the book is filled with factual errors but just because she is white, we don’t question these things.”

Asymmetry and Labeling in Reporting and Discourse

When reporting episodes concerning Christianity, journalists adopt a very professional and respectful tone. Consider the book Da Vinci Code, a mystery novel by Dan Brown published in 2003, tracing an alternative history of Christianity, a book that, as expected, received enormous attention. Hundreds of Christian organizations ranging from small outfits to CBN have responded angrily. A quick Internet search of reports of such criticisms shows the following language:

- “The book has been extensively denounced by many Christian denominations as an attack on the Roman Catholic Church.”

- “…mostly negative reviews from Catholic and other Christian communities.”

- “Critics accuse Brown of distorting and fabricating history.”

- “A Biblical Response was provided by …”

- “…presentation of religious ideas that some Christians regard as offensive”

- “Christian groups in many Asian nations have stepped up their protests …”

- “A Christian perspective…”

Notice how respectfully Christians are referred to in reports. None referred to upset Christians protesters as “fundamentalists”, “neo-Nazis” or “right-wing”ers. Those protesting Doniger’s book however attract a different kind of reporting.

The Time Magazine labels Dinanath Batra as a Hindu activist that has “arm-twisted” Doniger. In the article Hindu fundamentalists vs. Hinduism, USA Today introduces SBAC as a “Hindu Fundamentalist group”. Dinanatha Batra is an “upper caste man“. Dean Nelson of The Telegraph

reporting from Delhi stands to lose nothing by saying that “the book angered fundamentalists” and “fundamentalists have criticised the book”. He neither has the burden of reading the book, nor knowing anything about Hinduism, nor of India’s history. As a rule, these reports make not a single mention of how Doniger portrays Hinduism.

Calling Out the Labelers

Hindus must learn to identify when they are being labeled and call it out.

Reductio ad Hindutva

The moniker “Reductio ad Hitlerum”, was coined by Leo Strauss of University of Chicago, a predecessor of Doniger, to describe the following fallacy: If you do or like something that Hitler did, then you are also like Hitler. For example, if you are devoted to your nation, since Hitler was a nationalist, then you are like Hitler.

Wendy Doniger, in her response to the settlement, praises Penguin for taking on this book “knowing that it would stir anger in Hindutva ranks”. Notice how Doniger uses the by now familiar word “Hindutva”, a fashionable ammunition to invoke the threat of fundamentalism. She does what she knows always works well, i.e. scare Hindus into submission and then invoke fake victim hood. The truth is that her book stirs anger in all Hindus, not a special section of Hindus. Essentializing all Hindu voices as fundamentalist political views is a tactic that has been used to discourage Hindu identity or voice.

This type of labeling Hindus, who speak up to express their anguish and indignity when Hinduism is denigrated, as fundamentalists should be described as Reductio ad Hindutva – a logical fallacy of undermining an argument by association. The implication is the following: If you do anything that a Hindu fundamentalist would do (such as get angry, as Dean Nelson of The Teleghraph reports), then you are a Hindu fundamentalist. Among other things, since Hindu fundamentalists would come in support of Hinduism, any effort to support Hinduism is a sign of fundamentalism. The only way you could stop Doniger from slapping you with the charge of fundamentalism is if you stop standing up for Hinduism.

Ironically, the word Hindutva is a beautiful word that means ‘the essence of what a Hindu is’. In the Sanskrit language, the suffix ‘-tvam’ is equivalent to the suffix ‘-ness’ in English – used to indicate the attribute or nature of an object. For example, ‘kaṭutvam’ refers to the nature of being pungent, strong-scented or bitter, i.e. ‘bitterness’. ‘Samatvam’ indicates equanimity (‘sameness’) and ‘manushyatvam’ refers to the nature of being a ‘manushya’, human. Thus, Hindutvam means the nature of being a Hindu or that which makes a person or a thing Hindu. By definition, all Hindus have Hindutvam – just as Christians have Christness and Muslims have Islamness.

Anti-Hindu “scholars”, “journalists” and media have hijacked the traditional word “Hindutva” and ascribed the pejorative meaning of “Hindu nationalism” and associated with religious identity politics. Any effort on the part of Hindus to take a stand to show solidarity is labeled “saffronization”. Are Hindus not allowed any solidarity or group identity, to speak for their collective rights?

Hindus cannot seek comfort in thinking that they are not being compared to the likes of Hitler. New York Times recently called them “Taliban-like” forces.

Reductio ad Taliban

The New York Times, known for its penchant for India-bashing, Hindu-baiting and Modi-bashing (see my recent article), as expected, covered this episode. Notice how Ellen Barry once again resorts to quoting nobodies. She quotes “one writer” (whom she doesn’t name) referring to Dinanath Batra’s organization as “an unknown Hindu fanatic outfit” and given to “Taliban-like forces“. The word Taliban readily conjures vivid mental images of flying airplanes into skyscrapers, shooting blindfolded citizens, lashing men and women publicly, and chopping off the hands of innocent men. Why would a journalist of the New York Times find it right to use such threatening labels to describe a Hindu who voices a concern peacefully, using constitutionally-enabled legal means, and within the provisions of law? What burden does the non-Hindu

American journalist, serving as Moscow Bureau Chief writing about Hindus of India, have? She cleverly uses a picture of Batra alongside RSS stalwarts – enough to send deracinated Indians into a tailspin.

Dinanath Batra and his group had meticulously prepared their case after studying Doniger’s book thoroughly. They did not burn buses, loot shops, issue threats or a fatwa against Wendy Doniger. Their use of English may not be as sophisticated as that of Arundhati Roy‘s, but they followed the law for four years after which Penguin decided to voluntarily withdraw. Sandeep Balakrishna explains why this is not a free speech issue and Aravindan Neelakantan traces intellectualism and openness in historical Hindu responses to opposing worldviews and threats to Hinduism.

A few months ago, the store chain Costco apologized for labeling The Bible as “Fiction”. The media didn’t brand the protesting people as Christian Fundamentalists, just Christians. There was no media-led hue and cry about suppression of Freedom of Speech. Fourteen years ago, many will recall Doniger stating in a public lecture in 2000 that the “Bhagavad Gita is a dishonest Book”. When Hindus demanded an apology, they were promptly labeled as fundamentalists!

Prof. Doniger knows full well that Hindus followed the law by the book. So she blames Indian law. Immediately after her statement, Indian Sepoys – like faithful followers of the colonial masters – joined in the thousands to sign petitions to reform the Indian Constitution. I am reminded of General Dyer and tragedy of Jallianwala Bagh of 1919. One wonders where these free speech pontificators were when Harvard University chose to terminate the honorary professorship of Dr. Subramanian Swamy for his forthright talk on wiping out Islamic Terrorism. Or when the majority-discriminatory Communal Violence (Prevention) Bill was introduced by the Indian Parliament. On the contrary, the Catholic Church in Mumbai filed blasphemy charges under the same section 295A against Sanal Edamaruku, who attributed the miraculous water dripping at the crucifix to a leaking drainage. (He has since fled to Finland to escape a life sentence.) Let us see if these self-styled liberals offer a whimper of a protest to the recent news that google was asked to pull out a youtube video of an allegedly anti-Islam movie “Innocence of Muslims”.

“Donigeration”

The Hindu is indeed tired of being attacked within and outside her homeland but yet has no penchant for a Homeland security bill or a Patriot act. Would Prof Doniger joke at Chicago Airport that she has a bomb and test her first amendment rights? Would she write a History text about the violence, slavery, plunder, and rape of conquered women that the Holy Bible alludes to and be awarded academic Honors in the West or Israel? Has the US demanded action against Churches for Pedophilia and Money Laundering, and arrested Cardinals and Popes, and why is there no publicity of these criminal acts?

Only in India do we find that blatant denigration of Hindu deities by M. F. Hussain through his paintings or by Doniger’s writings gets applauded as an expressions of free speech. Lascivious depictions of Jesus in the US would never be condoned. The muted reaction to the fatwa against the Danish cartoonist for just one objectionable cartoon of Prophet Mohammad shows the blind-spots of all free-speech advocates.

In the 1940’s and 1950’s in the US when Communism was seen as a threat, John McCarthy’s speeches on alleged communist infiltration lead to a witch-hunt of anybody who was not anti-communist. Even though McCarthy was proved wrong and censured, it marked one of the most repressive times in American Politics of the 1900’s. The term ‘McCarthyism’ was born. I feel the need for another new term in the English Lexicon:

don·i·ger·ate

Transitive verb \ˈdo-ni-ˌgər-āt\ don·i·ger·ated, don·i·ger·ating

1 : to attack the religious sanctity of : denigrate <donigerate Hindu deities>

2 : to make a denigrating interpretation of anything held sacred: <donigerate modes of worship>

3 : to defame in the cloak of scholarship; to use the academic pulpit to denigrate a native tradition

4 : to make an institution out of victimizing ancient traditions

5 : to invoke fake victim-hood when criticized.

Conclusion

Hindus do not need a lecture on free speech, rather we need to speak freely. It is alright to get upset when Hinduism is defamed. It is alright to protest peacefully, contest and file lawsuits, and write – none of which makes fundamentalists of Hindus. The West has not figured out a way to accept ancient traditions that consider the world or nature as sacred, whose spiritual vision dissolves perceived differences between the individual, the world and God. It requires a paradigm-shift to appreciate that it is possible to sublimate one’s passions without suppressing them. America should focus on its past and address the guilt born of decimating the Native Indian traditions before obsessing over and developing crackpot theories of cultures they understand very little about. The western penchant to exoticize, sensualize and debase such traditions in the cloak of free speech or scholarship is a disease that will likely continue for a while. Utilizing their Indian Sepoys, entrenched establishments will threaten Hindus with words like fanatics, fundamentalists, right-wingers, fascists, Hindutva, saffron brigade. Hindus will learn not to take such sham threats seriously and in turn label the labellers.

Islam and Christianity have powerful hierarchical institutions that are also politically active. Unlike them, while Hindus have institutions called Mathas and Pithas some of which are millennia-old, none of them expected such vicious treatment and are not geared even for institutional protests, leave alone exercising political clout. The Acharya Sabha, the Apex body for Hindus, was formed precisely for giving Hindus a voice, but it is very much in its infancy. Until then, it is individuals and organizations that take up the cause for Hindus. Hence, Hindus should be proud of Dinanath Batra, SBAC and Monika Arora.

It is no wonder that Hindus are fighting back. Four years ago, Doniger’s book was shortlisted for an award by the National Book Critics Club in 2010. After dozens of intelligent letters like the following from Subroto Gangopadhyay and thousands of petition signatures, the award was blocked. These represent a refreshing rise in crisp scholarship by Hindus who challenge Western Universalism.

Such Hindu responses shouldn’t surprise Doniger. After all, Hindus are studying the Bhagavad Gita more than ever before. Was it not Prof. Doniger who said that “The Bhagavad Gita is not as nice a book as some Americans think… Throughout the Mahabharata … Krishna goads human beings into all sorts of murderous and self-destructive behaviors such as war?”

Shubham Bhooyaat

You may like

articles

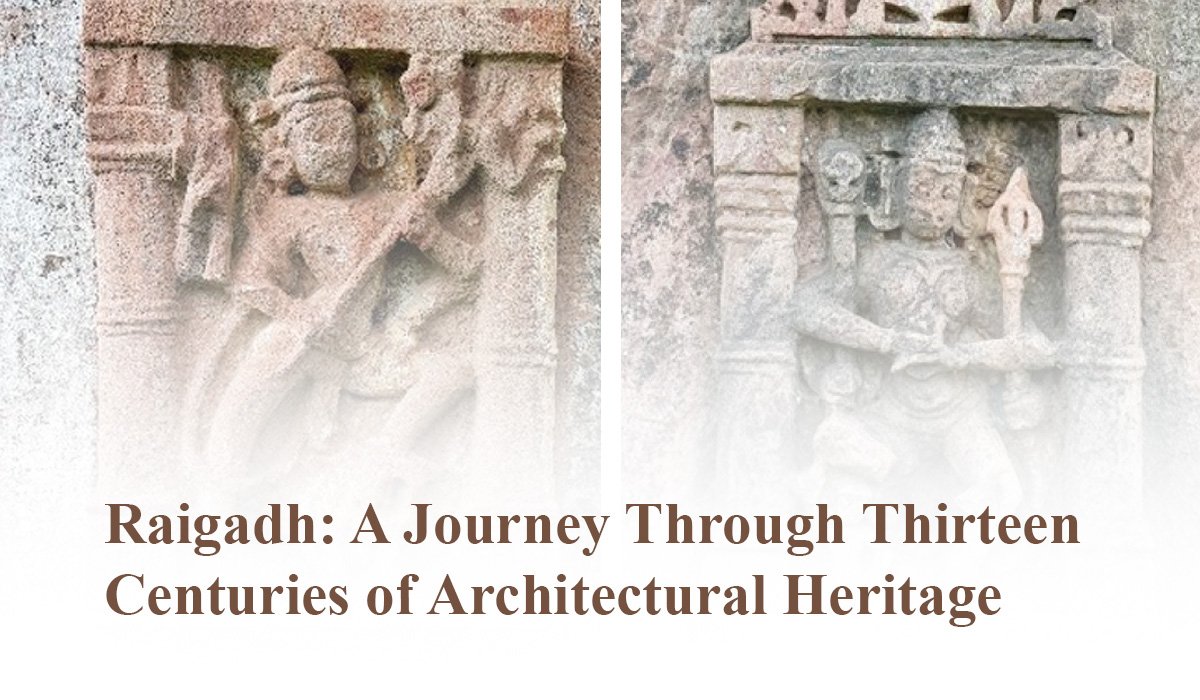

UNDERSTANDING THE CHRONOLOGY OF RAIGADH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE GIVEN TO ITS STRUCTURAL MONUMENTS

Published

4 days agoon

January 16, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

Raigadh: A Journey Through Thirteen Centuries of Architectural Heritage

Nestled in the Sabarkantha district of Gujarat, the small village of Raigadh (23°36’17” N, 73°10’42” E) stands as a remarkable open-air museum of Indian architectural evolution. From the late 7th century to the 20th century, this humble settlement has accumulated an extraordinary collection of structural monuments that chronicle the reign of multiple dynasties and the transformation of religious beliefs and practices. By studying Raigadh’s monuments, we can trace the architectural innovations, iconographical changes, and cultural shifts that shaped North Gujarat’s history.

The Maitraka Legacy: The Mota Mahadev Temple

The oldest surviving monument in Raigadh is the Mota Mahadev temple, dating to the late 7th century CE during the Maitraka period. This Shiva temple exemplifies the Phamsana architectural style, featuring a distinctive Ksoni or Gandharic-type Shikhara (spire). The original Maitraka design consisted of a Shikhara and a Garbhagriha (inner sanctum), adorned with intricate sculptures of Ganesha and Maithuna (amorous couple) figures that reveal the artistic sophistication of this ancient dynasty. What makes this temple particularly significant is its continuous religious importance. Centuries later, during the Solanki period (10th century), the temple underwent substantial renovations. The Solanki additions included a Mandapa (entrance hall) with a Kakshasana (bench-like structure), complete with plain pillars topped with lotus patterns. This evolution reveals how temples were actively modified across generations, adapting to changing worship practices. The temple boasts sculptures from both periods, including a standing Ganesha from the Maitraka era and later additions like a Nandi (bull mount of Shiva), Pranala (water channel), and a goddess figure, likely Parvati. Though the temple has undergone modern renovations with lime mortar and cement, it remains a living temple, worshipped especially during auspicious occasions like Mahashivaratri.

The Saindhava Contribution: Kashi Vishwanath Temple

The 9th century witnessed the construction of the Kashi Vishwanath temple during the Saindhava period, reflecting the dynasty’s influence in North Gujarat. Built entirely in sandstone, this temple showcases a Phamsana Vimana with a Ksoni Phamsanakara Shikhara—a pyramidal or diamond-shaped design that distinguishes it from contemporary structures. The east-facing temple follows an architectural plan featuring a Vimana with a sanctum and no ambulatory path, representing a distinct approach to temple design. The sculptural program of this temple deserves particular attention. The northern wall displays Andhakasuravedha, a four-handed form of Shiva depicted with a trident and the demon Andhakasura positioned above. The western wall features Bhairavi, the feminine counterpart of Bhairava, captured in an energetic Rudra Tandava (cosmic dance) with bent legs and an attending drummer. The southern wall houses Chamunda, a form of Katyayni and one of the Sapta Matrika (Seven Mothers), rendered in surprisingly human form rather than skeletal. These sculptures reveal sophisticated iconographical knowledge and demonstrate the 9th-century artistic tradition’s depth. Currently, the temple survives as a living sanctuary, though its sculptures show weathering, and structural elements like pillars and amlaka (stone finial) display signs of decay. It remains an active worship site on significant Hindu festivals, preserving unbroken continuity of devotion spanning over a millennium.

Innovation and Utility: The Solanki Stepwells

Contemporary with the Kashi Vishwanath temple’s later phases, the 10th-century Solanki period produced remarkable stepwells (Bhadra) that reflect advanced hydraulic engineering. These structures, constructed in sandstone with an east-west orientation, descend six storeys deep, featuring curved arches on each level. One stepwell includes a small chamber at its terminus, adorned with a Ganesha sculpture on its lintel, connecting utilitarian architecture with spiritual significance. The third storey houses a Chamunda sculpture whose stylistic qualities echo the iconographical changes occurring in this period. These stepwells appear strategically positioned near the Kashi Vishwanath temple, suggesting integrated temple complexes designed for both religious and practical purposes. The architectural features, particularly the pillar designs, parallel those found in the Solanki Mandapa of Mota Mahadev, indicating consistent construction methodologies across different monument types.

The Jain Testament: The Solanki Jain Temple

Built during the 11th or 12th century under Solanki patronage—likely under monarchs like Jayasimha Siddharaja or Kumarapal—the Jain temple dedicated to Sri Kunthunath (the seventeenth Jain Tirthankara) represents significant architectural complexity. The temple follows a comprehensive architectural plan including a Vimana, Garbhagriha, multiple Mandapas, and an Antrala (intermediate chamber). Sculptures of Sri Kunthunath and Vardhaman Mahavira adorn its walls, while a Vyali (mythical creature) appears on the lintel. Two inscriptions, written in Devanagari script, provide invaluable documentary evidence. The first, dated to Samvata 1717, records donations by Bhavanidas and his ancestors. The second mentions Lakha, identified as the sculptor of the Sri Kunthunath figure. These inscriptions document religious practices and preserve the names of patron families, offering rare glimpses into medieval Gujarati society. Despite its architectural sophistication, the temple currently stands in a ruined state, a poignant reminder of cultural heritage’s fragility.

Later Developments: Medieval and Modern Monuments

Subsequent centuries added new layers to Raigadh’s architectural narrative. The 14th-15th century Shakti temple, locally known as Repri Mata temple, reflects the Maru-Gurjara architectural style. The 17th-18th century Chhatri (cenotaph), dedicated to rulers of the Marwar dynasty governing Idar, stands on the village’s southern foothills in ruined condition. Most recently, the Goswami community, arriving in the early 20th century, established over 50 Samadhis (memorial structures), of which 28 remain today, representing modern funerary architecture and spiritual continuity.

Conclusion:

Reading History in Stone Raigadh’s monuments form an extraordinary chronological narrative spanning thirteen centuries. From the Maitraka Shiva temple to 20th-century Samadhis, these structures document the rise and fall of dynasties, the evolution of religious iconography, the permanence of worship, and the persistence of community memory. By preserving Raigadh’s architectural heritage, we conserve not merely buildings, but the lived history of Gujarat’s diverse populations and their enduring cultural values.

articles

Stones, Seals & Grants: Reweaving Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Published

4 days agoon

January 16, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

Stones, Seals & Grants: Understanding Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Introduction

For centuries, the Chalukya dynasty has been studied through the lens of royal conquest and centralized empires. However, recent archaeological and epigraphic discoveries are fundamentally reshaping our understanding of how power actually functioned in early medieval Deccan. Rather than viewing Chalukya authority as a top-down system of control, scholars now recognize it as a sophisticated network of practices—woven together through temple patronage, copper-plate grants, and carefully negotiated alliances with local elites. This shift in perspective reveals that Chalukya power was not simply inherited or conquered; it was continuously constructed, performed, and reinforced through everyday administrative practices, sacred architecture, and strategic land redistribution.

The Chalukya Dynasty: Rulers of a Networked Deccan

Historical Context and Geographic Reach

The Chalukyas (6th–12th centuries CE) emerged as one of the most significant dynasties of the Deccan region, ruling vast territories that encompassed both Western and Eastern domains. The Western Chalukyas controlled areas centered around Badami and later Kalyani, while the Eastern Chalukyas dominated the Vengi region. This geographical division was not a sign of weakness but rather a sophisticated administrative strategy that allowed the dynasty to maintain influence across diverse regions with distinct cultural, linguistic, and economic characteristics.

Beyond the Model of Centralized Empire

Traditional historical narratives have often portrayed medieval Indian dynasties as centralized empires with absolute monarchs wielding power from capital cities. The Chalukya case complicates this model significantly. Rather than a unified, monolithic state structure, Deccan power under the Chalukyas operated as a network of negotiated relationships. Local elites, temple institutions, agrarian communities, and emerging feudatory chiefs all played active roles in sustaining and legitimizing Chalukya rule. This networked approach enabled the dynasty to accommodate regional diversity while maintaining broader political cohesion—a model that proved remarkably effective across six centuries of rule.

Material Evidence: The Kodad Copper Plates and Mudimanikyam Temple

The Kodad Copper Plate (c. 918 CE)

One of the most significant recent discoveries is the Kodad Copper Plate, dated to approximately 918 CE during the reign of a Vengi Chalukya king. This inscribed plate is far more than a ceremonial artifact; it represents a crucial administrative document that reveals how power was systematically documented and disseminated.[1]

The Kodad plate records a coronation grant—an official allocation of land and privileges awarded to celebrate a royal succession. The text provides several layers of historical information: a detailed genealogy of the ruling family, specifications of land rewards granted to favored nobles and institutions, and explicit taxation clauses that clarified revenue rights and obligations. By examining such documents, we gain insight into how military service was converted into permanent landed privileges—a process that formalized social hierarchy and bound regional elites to the Chalukya crown through tangible economic benefits.

Significantly, the Kodad plate contains the earliest clear reference to the emerging Kakatiya chiefs, a lineage that would eventually establish its own powerful dynasty in the region. This notation illustrates how Chalukya inscriptions served as administrative records that tracked the rise of new regional powers, a dynamic relationship rather than static dominance.

The Mudimanikyam Panchakūta Temple (8th–9th century)

While inscriptions document administrative decisions, architecture demonstrates power in physical space. The Mudimanikyam temple complex in Telangana, constructed during the 8th–9th centuries, exemplifies the distinctive Chalukya approach to sacred architecture. The temple is remarkable for its unique five-shrine configuration—a design known as panchakuta (five towers)—which represents a sophisticated synthesis of architectural traditions.

The complex blends elements of both Kadamba and Nagara architectural styles, reflecting the cosmopolitan architectural culture of the Deccan. Rather than imposing a single standardized temple design across their empire, the Chalukyas appears to have encouraged regional architectural experimentation and adaptation. This flexibility strengthened their cultural authority because temples served dual purposes: they functioned as ritual centers for religious communities and simultaneously acted as tangible markers of royal presence and patronage. A Chalukya temple was not merely a place of worship—it was a statement of political legitimacy built into the landscape.

Expanding the Archaeological Picture: Brick Temples and New Discoveries

Brick Temple Foundations in Maharashtra (11th century)

Archaeological excavations in Maharashtra have uncovered the foundations of Chalukya-period temples constructed from brick rather than stone. This discovery, perhaps seemingly mundane, fundamentally challenges assumptions about Chalukya temple architecture. Historians had previously assumed that all significant Chalukya religious structures were built from stone, implying a uniform, monumental approach. The brick temples reveal a different reality: regional architectural experimentation and adaptation were deliberate policies, not exceptions.

The presence of diverse construction materials—stone for major complexes, brick for regional temples—suggests that Chalukya elites understood different building strategies for different contexts. Grand stone temples in Telangana and Karnataka communicated royal magnificence and permanence; more modest brick temples in Maharashtra demonstrated accessibility and cultural engagement with local communities. Together, these varied architectural strategies reinforced Chalukya authority across diverse populations and geographies.

New Copper Plate Grants from Telangana

Recently conserved copper plate grants from Telangana provide extraordinarily detailed records of agrarian administration and fiscal management. These plates record boundary descriptions with precision, specify tax divisions among different categories of land, and detail village allocations and their redistributions. Unlike the Kodad plate, which focuses on royal coronation, these records illuminate the administrative machinery of everyday governance.

These documents reveal a sophisticated understanding of land as a political instrument. Grants of land were not merely economic transactions; they were calculated acts of resource redistribution designed to secure and maintain the loyalty of local elites. Each plate can be read as evidence of deliberate fiscal policy intended to balance competing interests and consolidate authority. As the presentation notes, “land is equal to the currency of political negotiation” in the Chalukya context—a profound insight into the material basis of medieval power.

Methodology: How Scholars Reconstruct the Past

Understanding Chalukya power requires a multidisciplinary approach that synthesizes diverse types of evidence. Scholars examining this period employ several complementary research techniques:

Epigraphic Analysis: Scholars carefully translate and analyze copper plates and stone inscriptions, extracting genealogical information, administrative details, and references to contemporary personalities and places. This linguistic detective work reveals how ruling families represented themselves and legitimized their authority through written language.

Architectural Study: Detailed examination of temple plans, stylistic elements, construction techniques, and spatial organization provides evidence of aesthetic choices, regional influences, and the pragmatic concerns of builders. Architecture speaks when documents are silent.

Prosopography: This technique involves systematically tracking named individuals mentioned in inscriptions—nobles, officials, priests, and merchants—across multiple documents. By tracing individuals through space and time, scholars reconstruct networks of power and patronage that connected royal courts to regional societies.

Archaeological Context: Careful excavation, material analysis, and scientific dating techniques (such as radiocarbon analysis) ground inscriptions and architecture in chronological frameworks and material reality.

Synthesis: The final step integrates all this evidence. When copper plate texts are cross-linked with temple foundations, genealogical references with architectural styles, and administrative records with excavation reports, a fuller picture emerges—one that shows how Chalukya authority was constructed through ritual performance, economic distribution, and everyday administrative practice rather than brute force alone.

Rewriting Chalukya History: From Royal Chronicles to Institutional Practice

The Institutional Turn

Recent discoveries fundamentally alter how we conceptualize Chalukya rule. Rather than reading chronicles of royal conquest and succession, scholars now focus on the everyday institutions that sustained power: the bureaucratic systems that recorded grants, the temple organizations that managed resources, the elite networks that mediated between royal authority and local communities, and the agricultural base that generated the surplus wealth necessary to support courts, temples, armies, and administration.

This shift from “top-down” models of power to “institutional” models represents one of the most significant methodological changes in medieval Indian historiography. It acknowledges that power operates through systems and relationships, not merely through the decisions of individual rulers.

The Kodad Plates and Legal Transformation

The Kodad plates exemplify this institutional approach. These documents reveal how military service could be converted into permanent landed privileges through legal text and bureaucratic procedure. A warrior rewarded by a Chalukya king received not merely a temporary gift but a heritable right—a foundation for dynasty-building at the regional level. Over generations, such grants accumulated and transformed military subordinates into quasi-independent feudatory chiefs. This process, documented in the Kodad plates and similar inscriptions, explains how large empires gradually fragmented into smaller principalities while maintaining the ideology of a unified system.

Temple Building as Political Strategy

The Mudimanikyam and brick temple discoveries demonstrate that both monumental and modest temple construction were deliberate political strategies. Temples were not merely expressions of religious piety; they were tools for projecting political and cultural presence into territories where royal courts might be geographically distant. A well-constructed, beautifully designed temple in a regional town served as a permanent advertisement of royal patronage and cultural sophistication.

Agrarian Administration and Elite Loyalty

The newly conserved copper plate grants from Telangana provide the most granular evidence for how Chalukya power was maintained through agrarian management. These plates record:

- Boundary specifications: Precise definitions of land parcels, indicating sophisticated cartographic understanding

- Tax divisions: Categories of land taxed at different rates, reflecting different agricultural potentials and uses

- Village allocations: Systematic distribution of resources among communities and individuals

These records illuminate a political economy where land grants were carefully calibrated to reward loyal subordinates while maintaining agricultural productivity. An elite family granted fertile river-valley land would prosper and remain grateful; a family granted marginal lands might seek alliance elsewhere. The grants thus represent calculated political decisions, not arbitrary donations. Each plate is a small window into the pragmatic calculations of medieval power.

Conclusion: Toward a More Complete Understanding

The discovery and analysis of Kodad copper plates, Mudimanikyam temple, brick temple foundations, and newly conserved Telangana grants collectively reshape our understanding of the Chalukya dynasty. These material remains demonstrate that Chalukya power was not the product of centralized royal authority imposing itself from above. Rather, it emerged from a sophisticated web of interconnected practices: inscriptions that documented decisions and fixed them in public memory, temples that physically manifested royal piety and authority, land grants that bound regional elites through economic self-interest, and administrative networks that coordinated diverse territories.

The Kodad plates show how legal texts formalized the conversion of military service into hereditary privilege, thereby enabling the gradual emergence of regional feudatory dynasties. The Mudimanikyam temple complex and brick temple foundations demonstrate that Chalukya elites deliberately employed architecture—whether monumental or modest—to express political presence and engage with diverse communities across their vast territories.

Most importantly, these discoveries shift scholarly focus from courtly chronicles and royal conquests to the everyday institutions that sustained Chalukya rule: the scribes who wrote grants, the priests who consecrated temples, the administrators who managed villages, and the elites who negotiated power within a system of mutual obligation and benefit.

Future research in archives, excavation of additional temple sites, and scientific analysis of material remains will continue to illuminate these institutional foundations of medieval power. Yet already, these recent discoveries make clear that understanding the Chalukyas requires attending not to military campaigns alone but to the mundane instruments—stones, seals, and grants—through which authority was actually constructed and maintained across six centuries of rule in the medieval Deccan.

References

[1] Kodad Copper Plate (c. 918 CE). Records coronation grant of Vengi Chalukya king with genealogy, land rewards, and taxation clauses. Earliest clear reference to emerging Kakatiya chiefs.

Further Reading

- Mudimanikyam Panchakūta Temple (8th–9th century). Five-shrine Chalukya-style complex in Telangana with architectural blend of Kadamba and Nagara traditions.

- Brick Temple Foundations (11th century, Maharashtra). Archaeological evidence of regional architectural adaptation and experimentation.

- Copper Plate Grants (Telangana). Records of agrarian administration, tax divisions, and village allocations demonstrating detailed fiscal management strategies.

articles

Archaeological Wealth of Sirsee Village

Published

7 days agoon

January 13, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

Sirsee Village in Lalitpur district, Uttar Pradesh, reveals a treasure trove of archaeological remains spanning centuries. This small settlement, rich in sculptures, hero stones, temple fragments, and a moated fort, connects to broader historical networks of the Gupta, Gurjara-Pratihara, and Bundela periods. Recent documentation highlights its untapped potential for understanding regional cultural continuity.

Location and Context

Sirsee lies 28 km from Lalitpur, 54 km from Deogarh, 10 km from Siron Khurd (ancient Siyadoni), and 24 km from Talbehat. Nestled amid key historical centers from the Gupta (4th-6th century CE) and post-Gupta eras, it sits near trade routes like the Jhansi-Bhopal path. Nearby Siyadoni, founded in the Gurjara-Pratihara period (8th-11th century CE), underscores Sirsee’s role in economic and cultural exchanges.

Archaeological Sites

Researchers identified seven key locations with artifacts, many in deteriorated states yet revered by locals.

Site 1: Features a hero stone and temple members, hinting at martial commemorations and religious structures.

Site 2: Includes a fort with Surya and Ganesha sculptures, Bundela-style jharokha (balcony), and a temple complex encircled by a moat.

Site 3: Hosts a Mahishasur Mardini (Durga slaying the buffalo demon) sculpture and mural paintings.

Site 4: Contains broken sculptures, an inscription, hero-stone fragments, and a Hanuman figure near temple ruins.

Site 5: Displays additional broken sculptures and ruins, possibly linked to later shrines.

Site 6: Encompasses another temple complex with structural remnants.

Site 7 (implied): Sati stambha (memorial pillars) and further fragments, indicating post-medieval practices.

Satellite imagery from Google Earth (2025 Airbus and Maxar) maps these sites, showing the fort’s scale (up to 200m) and strategic layout.

Key Artifacts

Sculptures dominate, including broken icons of deities like Mahishasur Mardini, Surya, Ganesha, and Hanuman, often in black stone or similar material. Hero stones and sati stambhas suggest battles and sati rituals, common in medieval India. Inscriptions, though fragmented, may reveal patronage or events, while temple fragments point to Shaivite or Vaishnavite worship. Bundela-style elements, like jharokhas, link to 16th-18th century Rajput architecture in Bundelkhand.

Historical Significance

Earliest occupation likely dates to the 11th-12th century CE, based on sculptural styles, though proximity to Gupta sites suggests earlier influences. The fort implies defensive needs, possibly tied to trade route conflicts or regional power struggles. Hero stones evoke battles, aligning with Pratihara-era warfare, while the moat and location near Siyadoni indicate a trade or worship hub. Continuity persists as villagers worship these relics, blending ancient heritage with living tradition.

Research Questions

The presentation raises critical queries: What defines Sirsee’s occupation timeline? Why build a fort here? Did trade or pilgrimage drive its prominence? Evidence of wars? Connections to Gupta, Pratihara, or Bundela rulers? No systematic study exists, urging documentation to trace settlement origins and evolution. Yashraj Panth, Research Associate at Sharva Purattav Solution Private Limited, calls for further exploration.

Sirsee embodies Bundelkhand’s layered past, from medieval sculptures to Bundela forts, demanding preservation and study.

UNDERSTANDING THE CHRONOLOGY OF RAIGADH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE GIVEN TO ITS STRUCTURAL MONUMENTS

IHAR Member Presents Research at 2nd International Conference on Guru Padmasambhava, Odisha

Stones, Seals & Grants: Reweaving Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Archaeological Wealth of Sirsee Village

Unveiling Ancient Footprints: Archaeological Discovery in the Khairi-Bhandan River Basin of Odisha

Bharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

Bringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

Panel Discussion on Sati

Bengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

Panel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution

Debugging the wrong historical narratives – Vedveery Arya – Exclusive podcast

The Untold History Of Ancient India – A Scientific Narration

Some new evidence in Veda Shakhas about their Epoch by Shri Mrugendra Vinod ji

West Bengal’s textbooks must reflect true heritage – Sahana Singh at webinar ‘Vision Bengal’

Bringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

Trending

-

Events2 years ago

Events2 years agoBharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

-

Videos3 years ago

Videos3 years agoBringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

-

Videos11 years ago

Videos11 years agoPanel Discussion on Sati

-

Events10 months ago

Events10 months agoBengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

-

Events8 months ago

Events8 months agoPanel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution