While Pakistan struggles towards its goal of achieving a homogenous monoculture with Islamism at its core, India has struggled equally to define nationalism, within its tradition of worship at the altar of diversity. Both of these imagined utopias can become delusional, self- contradictory and inconsistent with a functional nation state. In Pakistan, the fissiparous tendencies are due to forced oppression of ancient cultural and ethnic identities. In India the same tendencies are due to pretension that there was no ancient Indian cultural identity, but only a subset of invader or migratory identities, each of which must be promoted irrespective of the cost to the nation.

articles

Pakistan’s Zero Sum Game – Some Historical Perspectives – Part II

Published

9 years agoon

By

ihar

Author: Dr. Subroto Gangopadhay

Press Release: indiafacts.org/pakistans-zero-sum-game-historical-perspectives-part-ii/

In the concluding part of our series, we describe Pakistan’s role in Khalistan and continuation of Operation Tupac, beginning with the theocratic cleansing of Kashmiri Hindus, all the way upto Uri massacre, with the major events in between. Pakistan is consistent in its goals and India’s response equally consistent with its flawed thinking.

Sikh discontent spurs Khalistani movement

As East Pakistan’s civil war of independence entangled India, in 1971, another important movement was silently taking shape among the Sikhs, the largest Indian diaspora that migrated to the UK, US and Canada in the period that preceded and followed Indian Independence in 1947. Working as drivers, conductors, transporters, laborers and farmers, they retained their strong roots. Gradually, they began to face discrimination, especially in the UK where employers demanded that they remove their turbans, beards and other symbols of personal faith. Harassed and hurt, they went to the Indian High Commission seeking help. This was not forthcoming as Prime Minister Nehru’s Government, unlike the Israelis, had a hands-off approach to the diaspora, particularly after they accepted foreign citizenship. Fearful that there was no power to defend their faith, the “Sikh Home Rule” movement was launched by the UK based Sikh bus drivers and conductors, under Charan Singh Prachi’s leadership. Subsequently, Dr. Jagjit Singh Chauhan, former finance minister and deputy speaker of Punjab migrated to the UK and assumed leadership of the movement. He renamed the “Sikh Home Rule” into the movement for “Khalistan” that took birth just prior to the Bangladesh liberation war of 1971.

Pakistan aligns with anti-Indian Khalistani movement

Even prior to Chauhan’s arrival in UK, the Pakistani Embassy and the US embassy in London, had established a working relationship with the Sikh home rule movement. The arrival of Chauhan, added momentum. Chauhan got good exposure in US as the CIA and ISI started their own campaign against India, alleging human rights violations by India against Sikhs in Punjab and Government indifference to the plight of diaspora in the west. This PSYWAR campaign countered Indira Gandhi’s attempt to draw the world’s attention to the genocide in East Pakistan. Henry Kissinger, the then director of the National Security Council, had his staff manage Chauhan’s media exposure. On October 13, 1971, an advertisement in the New York Times called for creation of the new state of Khalistan. The advertisement was paid for by the Pakistani Embassy in Washington DC, as per Indian intelligence. President Yahya Khan invited Chauhan, warmly received him and helped him gain stature as the leader of the Khalistani movement. The CIA and ISI propaganda campaign on behalf of Khalistan continued, until 1977 when Indira Gandhi lost the election to Morarji Desai in response to her enacting the Emergency Rule in India in 1975.

Zia- Hul- Haq usurped power in 1977, became President of Pakistan in 1978 and forged close friendships with Khalistani secessionist leaders, such as Ganga Singh Dhillon in US. ISI became more interested in the new emerging militant Sikh Organizations such as Dal Khalsa, Babbar Khalsa and International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF). Gajendra Singh of Dal Khalsa hijacked an Indian airlines flight to Lahore, in 1981. The plane and passengers were returned, but not the perpetrator. Gajendra Singh was asked to stay on at Nankana Sahib (80 Kms from Lahore), the birthplace of Guru Nanak and one of the holiest of Sikh pilgrimages, so that he could interact with visiting pilgrims and radicalize them. He was eventually tasked with looking after camps in Pakistani Punjab and NWFP, established to train Khalistani terrorists. The terrorists were armed by the ISI with weapons and improvised explosive devices thanks to the flow of arms from the US, for Afghan Mujahideens and free flow of funds from the US and Saudi Arabia. With wholehearted support from Zia ul Haq and ISI in the 80s, Sikh militancy flourished.

Khalistani terrorism peaks with Pakistani support

Indira Gandhi authorized Operation Bluestar in June 1984, as conservative measures failed to persuade entrenched militants to vacate the Golden temple complex. This was a massive operation to clear the Golden Temple of assembled militants under the command of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. A large number of lives were lost, the holy shrine of Akal Takht was seriously damaged and a deep wound was inflicted on the Sikh psyche. In October 1984, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards from Delhi Police. A shameful collapse of law and order followed in Delhi as news of the Prime Minister’s assassination spread. Rampaging mobs massacred numerous innocent Sikhs, destroyed their property and terrorized them in the national capital, with the Congress Government seemingly complicit. The Sikhs, among the greatest defenders of India, recoiled in horror and still seek justice. Pakistan-supported Khalistani militants swore revenge. Babbar Khalsa operatives based in Vancouver planted bombs that exploded on the Air India flight, Kanishka in 1985 killing 307 passengers and 22 crew members off the Irish Coast. Simultaneously, two other passengers at NarIta Airport in Tokyo succumbed to explosions in luggage loaded at Vancouver. The mastermind, of these attacks, Talwinder Singh Tomar, the head of Babbar Khalsa of Canada, escaped from Canada and found sanctuary in Pakistan. Lal Singh, the leader of International Sikh youth federation, who hatched a plot to assassinate Rajiv Gandhi the same year, on his state visit to US as Reagan’s guest too escaped to Pakistan.

Operation K-K winds down and Operation Tupac winds up

At home, General AS Vaidya, the Chief Of Staff of Indian Army and the executor of Operation Bluestar in 1984 retired on 31 January 1986 after which he was gunned down in Pune, on Aug 10, 1986, by Sikh extremists. The fires of Khalistan burned for more than ten years after that, though it is claimed Benazir Bhutto did not carry forward Zia’s policy despite ISI chief Hamid Gul’s advice to her that keeping Punjab active would be equivalent to maintaining two divisions in Punjab at no expense to the Pakistani tax payer. Pakistani support of Khalistan was retribution for the loss of the 1971 war. Besides, destabilization of Punjab would help Pakistan annex Kashmir with greater ease. The ISI code named this combined strategy Operation K-K. The Punjab militancy gradually began to lose steam in the 90s during Prime Minister Narasimha Rao’s tenure. Still, the Mumbai blasts of 1993 remained as a stark reminder of Pakistan’s commitment to the use of terror. While the Khalistan movement scaled down, Kashmir erupted and Operation Tupac gained strength.

Theocratic cleansing of Kashmiri Hindus within Hindu-majority India

As opposed to Operation Gibraltar, Operation Tupac used the new Jihadi Militia instead of disguised Pakistani Army regulars. It was, and is, a well-sustained, low cost, well-executed project of Kashmir’s annexation, through terrorism and insurgency. The first spectacular success of Operation Tupac was cleansing of the Kashmiri Pandits from the land of their forefathers. In 1986, Ghulam Mohammed Shah seized power from his brother-in-law, Farooq Abdullah, and proceeded to construct the famous Shah Masjid within the premises of an ancient Hindu Temple in the secretariat area of Jammu. The people protested, and the incumbent Chief Minister, retaliated by instigating people in the valley proclaiming “Islam Khatrey Mein Hai”. The Muslims went on a rampage and the Shah government was dismissed by Jagmohan, the Governor, in 1986. The Islamists lost the Kashmir election in 1987 (as in 1983). This was followed by launching of Tupac in 1988, as the free will of Kashmiris was not acceptable to Pakistan.

The cleansing of Pandits began with the murder of prominent Hindu citizens (such as Tika Lal Taploo by JKLF), followed by open threats to Hindus to leave their home and hearth from the terror proxies of Pakistan such as Hizb- ul Mujahideen. The Hizbul asked Hindus to leave, through open advertisements in local papers such as Aftab and Al Safa. During the administration of Farooq Abdullah in 1990, acting upon the advice of Mufti Muhammad Saeed, Prime Minister VP Singh re- appointed Jagmohan as the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir. The same day, January 19, 1990, Farooq Abdullah resigned as Chief Minister, as anticipated by Mufti Muhammad. A single day’s power hiatus with a Governor en route and no Chief Minister, proved fateful. On that day, Dec 19, 1990 Islamic chants echoed in the valley and Muslim crowds wielding guns ran amok. Hindus who survived the night had no recourse but to leave the land where their forefathers had lived millennia before Islam’s birth. This was the most shameful example of a government abdicating responsibility to its citizens, making them refugees within their own country. Operation Tupac built upon this unbelievable victory against a nation of one billion people. This was not just an ethnic cleansing. This was a theocratic cleansing by a Majority Muslim community of a minority Hindu community of the same ethnicity, within a Hindu majority nation.

Pakistani amends constitution to persecute Ahmadiyas

It should be no surprise that Pakistan had done the same theocratic cleansing not only to its own Hindu population, but even its Ahmadiya (declared Non Muslim by Pakistani Legislators in 1974), Shia and Christian populations. Pakistan, as per the second constitutional amendment enacted in 1963, became the Islamic Republic Of Pakistan. In 1974, it became a state where the parliament itself took upon the religious duty of excommunication. Dr. Abdus Salam, one of the world’s greatest theoretical physicists, father of Pakistan’s Science and Technology (including Nuclear Program) and a member of the Ahmadiya community, left Pakistan in protest against the Z A Bhutto Govt, declaring Ahmadiyas to be non-Muslims, through Parliamentary legislation in 1974.

ISI-sponsored terrorist organizations multiply

Focusing on Kashmir, the ISI systematically created Lashkar-e-Taiba, Jaish- e-Mohammed and Harkat- ul- Mujahideen, while supporting Indian Mujahideen, and Hizbul Mujahideen. Jammu Kashmir Liberation front (JKLF) had conditional support, which was withdrawn during periods when they eschewed violence or demanded an independent Kashmir. This undercuts Pakistani claims of support to Kashmiri self-determination and points to the larger geopolitical aims of the Pakistan or Sino-Pak axis.

In 1984 India gained territory in the Siachen Glacier conflict, the highest battleground of the world at 20,000 feet. Operation Meghdoot gave India control of the unmarked Glacier North of the Ceasefire line between India and Pakistan that terminated at NJ 9842. The ceasefire at Siachen took effect in 2003.The battle was the result of improper cartography besides Pakistani Government, granting permits to foreign teams to climb the glacier, implying control of an unmarked area.

India captured Maulana Masood Azhar, of Harkat –ul- Mujahideen in 1994. An early attempt by Al Faran in 1995, to secure his release in exchange for kidnapped foreign tourists failed. Success finally came for HuM in 1999 when the Vajpayee Government released Azhar, Omar Sheikh and Mustaq Ahmed Zargar, in exchange for release of the 192 passengers and crew of hijacked flight IC 184. Azhar did not return to HUM, but went on to establish the Jaish-e-Mohammed in 2000, a group that is more radical that HuM and perhaps the deadliest terror group in Kashmir. Omar Sheikh arranged funds for Mohammed Atta, a key conspirator of 9/11 attacks in the US and was also involved in the kidnapping and beheading of Daniel Pearl. Azhar remains a public figure in Pakistan. JeM was banned officially, even in Pakistan since 2002, but merely changed its name to Khuddam-ul-Islam. JeM’s avowed aim is to merge Kashmir with Pakistan and through the Kashmir gateway enter India to liberate Indian Muslims and drive away non-Muslims from the subcontinent, including Americans.

Pakistan successfully executes plan to bleed India by a thousand cuts

1999 saw a spectacular strategic success for Operation Tupac at Kargil. Winters in Kargil are harsh and by a gentleman’s agreement both Indian and Pakistani forces used to withdraw from their bunkers in winter and return only in summer. Musharraf and ISI betrayed India, while Vajpayee negotiated peace. Pakistani troops and irregulars captured unoccupied Indian positions in the winter of 1998-1999. RAW was caught napping and Indians only got wind of it, when shepherds informed Indian military about strangers occupying their bunkers. The Kargil War was fought in the summer of 1999. India won the war though it was an embarrassing diplomatic and intelligence failure for India. Kargil was thought to be a Siachen payback.

The Indian Parliament attacks in 2001 was an effective fidayeen strike by the JeM and LeT under the guidance of the ISI, that killed 14 people including 5 terrorists. Pakistan had by this time become a nuclear power. ISI had a role here as well. The agency had smuggled Abdul Qadir Khan from Holland from where the sensitive technology was stolen. He had, as it emerged, created a clandestine network for the proliferation and exchange of nuclear technology and material with China, Iran, North Korea and Libya. From the standpoint of Pakistan, becoming a nuclear power was a dream come true. Though, the establishment formally laid the blame for illegal proliferation at A Q Khan’s door, it begs the question why A Q Khan is the only person in the history of Pakistan, who has been awarded the country’s highest civilian honor Nishan-E-Imtiaz twice (1996 and 1999) under two different regimes, after having received the Hilal- E- Imtiaz, the nation’s second highest honor earlier in 1989. Even though, he was alleged to have sold nuclear secrets unknown to the state, no money was ever found and the scientist lived on modest means. It is hard not to see the ISI’s unseen hand here.

The feather in Pakistan’s cap was 26/11 Mumbai attacks by the LeT in 2008. This massive, daring attack was systematically planned over a long time. This attack caught Indian security and law enforcement flat footed. It took days for the country to quell the attack and neutralize the terrorists. By then, 161 Indian citizens had been executed, one of Mumbai’s iconic landmarks turned into a battlefield while India was caught between mourning the dead and defending its honor in full view of the world. The weakness in the system was exposed again, and lack of consequences, convinced Pakistan of India’s paralyzed resolve. While all the attackers ultimately died, the puppet masters continue their work unhindered in Pakistan. India had been invaded on this occasion through the seas.

The network between Pakistani Military, intelligence agencies, Jihadi terror affiliates and their Indian extensions like Indian Mujahideen, evolved over decades. Their plan to bleed India by a thousand cuts, by and large has been successful.

Pathankot and Uri attacks in 2016 were higher milestones for the continuing operation Tupac, because these were attacks on large fortified Indian military bases and not soft civilian targets. Their significance and message is clear. Pakistan remains convinced that an escalating terror strategy is not only feasible but advisable, given not only India’s tepid verbal responses to terrorism, but its inability to hold on to the gains of conventional war. The one aberration of a surgical strike has bucked the trend and sowed come confusion in Pakistan while the expected clarity in India has been obscured by the ensuing politics.

Large swathes of the Indian politicians and media inflict their own thousand cuts on the nation. This will continue until mechanisms are found to reduce their disproportionate power over the nation’s destiny. The electorate in India will again have to prove more sagacious than the forces manipulating them.

Mohammed bin Qasim has a place of glory in the history of Pakistan while his memory has dimmed in India. It is worth remembering that there were 14 Arab expeditions to Sindh and neighboring parts as recounted by GM Syed, prior to the eventual success of Qasim in 712 AD and the entry of Arab Imperialism on Indian shores. Qasim was 17 when he attacked Sindh. Indians often take pride in the valor of their defending Kings from Raja Dahir Sen to Prithviraj Chauhan. The Islamic Republic of Pakistan correctly interprets their version of history as the saga of invading heroes of Islam, who keep attacking until they conquer. Pakistan’s Kashmir policy reflects this historical understanding. India’s flawed defensive response is equally consistent with its own historical perspective. India makes heroes of martyrs and Pakistan adores only victors.

Conclusions:

*Perpetual defense is a doomed strategy. Qasim came in 711CE after fourteen futile earlier expeditions by others, and succeeded. Thirteen centuries is a long time to learn a simple historical fact that a persistent offense will eventually overcome the defense. Operation Tupac is succeeding and persistence will lead to victory.

* Nations can only survive history by learning to win when challenged. In any war it is preferable to be a decisive victor than a valorous martyr. Strength dissuades enemies, weakness is inviting to them.

* Citizens who do not hold the nation above themselves are fundamentally allies of the nation’s enemies.

* Solutions to problems between nations exist only if they have a common framework. Otherwise, stability is determined by power hierarchies.

* For Pakistan this is a zero sum game, retreat is not an option.

The author thankfully acknowledges the contribution of Sahana Singh and Rajkumar Vedam of IHAR to this series.

Image Credit: PIB

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

You may like

articles

UNDERSTANDING THE CHRONOLOGY OF RAIGADH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE GIVEN TO ITS STRUCTURAL MONUMENTS

Published

4 days agoon

January 16, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

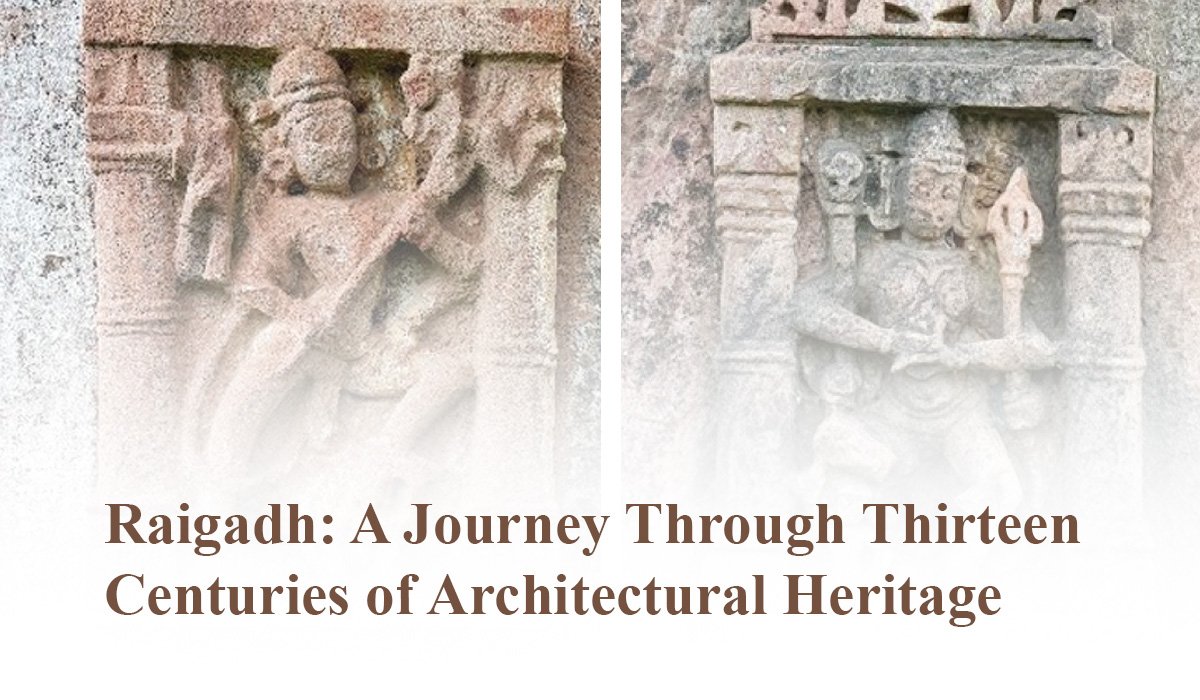

Raigadh: A Journey Through Thirteen Centuries of Architectural Heritage

Nestled in the Sabarkantha district of Gujarat, the small village of Raigadh (23°36’17” N, 73°10’42” E) stands as a remarkable open-air museum of Indian architectural evolution. From the late 7th century to the 20th century, this humble settlement has accumulated an extraordinary collection of structural monuments that chronicle the reign of multiple dynasties and the transformation of religious beliefs and practices. By studying Raigadh’s monuments, we can trace the architectural innovations, iconographical changes, and cultural shifts that shaped North Gujarat’s history.

The Maitraka Legacy: The Mota Mahadev Temple

The oldest surviving monument in Raigadh is the Mota Mahadev temple, dating to the late 7th century CE during the Maitraka period. This Shiva temple exemplifies the Phamsana architectural style, featuring a distinctive Ksoni or Gandharic-type Shikhara (spire). The original Maitraka design consisted of a Shikhara and a Garbhagriha (inner sanctum), adorned with intricate sculptures of Ganesha and Maithuna (amorous couple) figures that reveal the artistic sophistication of this ancient dynasty. What makes this temple particularly significant is its continuous religious importance. Centuries later, during the Solanki period (10th century), the temple underwent substantial renovations. The Solanki additions included a Mandapa (entrance hall) with a Kakshasana (bench-like structure), complete with plain pillars topped with lotus patterns. This evolution reveals how temples were actively modified across generations, adapting to changing worship practices. The temple boasts sculptures from both periods, including a standing Ganesha from the Maitraka era and later additions like a Nandi (bull mount of Shiva), Pranala (water channel), and a goddess figure, likely Parvati. Though the temple has undergone modern renovations with lime mortar and cement, it remains a living temple, worshipped especially during auspicious occasions like Mahashivaratri.

The Saindhava Contribution: Kashi Vishwanath Temple

The 9th century witnessed the construction of the Kashi Vishwanath temple during the Saindhava period, reflecting the dynasty’s influence in North Gujarat. Built entirely in sandstone, this temple showcases a Phamsana Vimana with a Ksoni Phamsanakara Shikhara—a pyramidal or diamond-shaped design that distinguishes it from contemporary structures. The east-facing temple follows an architectural plan featuring a Vimana with a sanctum and no ambulatory path, representing a distinct approach to temple design. The sculptural program of this temple deserves particular attention. The northern wall displays Andhakasuravedha, a four-handed form of Shiva depicted with a trident and the demon Andhakasura positioned above. The western wall features Bhairavi, the feminine counterpart of Bhairava, captured in an energetic Rudra Tandava (cosmic dance) with bent legs and an attending drummer. The southern wall houses Chamunda, a form of Katyayni and one of the Sapta Matrika (Seven Mothers), rendered in surprisingly human form rather than skeletal. These sculptures reveal sophisticated iconographical knowledge and demonstrate the 9th-century artistic tradition’s depth. Currently, the temple survives as a living sanctuary, though its sculptures show weathering, and structural elements like pillars and amlaka (stone finial) display signs of decay. It remains an active worship site on significant Hindu festivals, preserving unbroken continuity of devotion spanning over a millennium.

Innovation and Utility: The Solanki Stepwells

Contemporary with the Kashi Vishwanath temple’s later phases, the 10th-century Solanki period produced remarkable stepwells (Bhadra) that reflect advanced hydraulic engineering. These structures, constructed in sandstone with an east-west orientation, descend six storeys deep, featuring curved arches on each level. One stepwell includes a small chamber at its terminus, adorned with a Ganesha sculpture on its lintel, connecting utilitarian architecture with spiritual significance. The third storey houses a Chamunda sculpture whose stylistic qualities echo the iconographical changes occurring in this period. These stepwells appear strategically positioned near the Kashi Vishwanath temple, suggesting integrated temple complexes designed for both religious and practical purposes. The architectural features, particularly the pillar designs, parallel those found in the Solanki Mandapa of Mota Mahadev, indicating consistent construction methodologies across different monument types.

The Jain Testament: The Solanki Jain Temple

Built during the 11th or 12th century under Solanki patronage—likely under monarchs like Jayasimha Siddharaja or Kumarapal—the Jain temple dedicated to Sri Kunthunath (the seventeenth Jain Tirthankara) represents significant architectural complexity. The temple follows a comprehensive architectural plan including a Vimana, Garbhagriha, multiple Mandapas, and an Antrala (intermediate chamber). Sculptures of Sri Kunthunath and Vardhaman Mahavira adorn its walls, while a Vyali (mythical creature) appears on the lintel. Two inscriptions, written in Devanagari script, provide invaluable documentary evidence. The first, dated to Samvata 1717, records donations by Bhavanidas and his ancestors. The second mentions Lakha, identified as the sculptor of the Sri Kunthunath figure. These inscriptions document religious practices and preserve the names of patron families, offering rare glimpses into medieval Gujarati society. Despite its architectural sophistication, the temple currently stands in a ruined state, a poignant reminder of cultural heritage’s fragility.

Later Developments: Medieval and Modern Monuments

Subsequent centuries added new layers to Raigadh’s architectural narrative. The 14th-15th century Shakti temple, locally known as Repri Mata temple, reflects the Maru-Gurjara architectural style. The 17th-18th century Chhatri (cenotaph), dedicated to rulers of the Marwar dynasty governing Idar, stands on the village’s southern foothills in ruined condition. Most recently, the Goswami community, arriving in the early 20th century, established over 50 Samadhis (memorial structures), of which 28 remain today, representing modern funerary architecture and spiritual continuity.

Conclusion:

Reading History in Stone Raigadh’s monuments form an extraordinary chronological narrative spanning thirteen centuries. From the Maitraka Shiva temple to 20th-century Samadhis, these structures document the rise and fall of dynasties, the evolution of religious iconography, the permanence of worship, and the persistence of community memory. By preserving Raigadh’s architectural heritage, we conserve not merely buildings, but the lived history of Gujarat’s diverse populations and their enduring cultural values.

articles

Stones, Seals & Grants: Reweaving Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Published

4 days agoon

January 16, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

Stones, Seals & Grants: Understanding Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Introduction

For centuries, the Chalukya dynasty has been studied through the lens of royal conquest and centralized empires. However, recent archaeological and epigraphic discoveries are fundamentally reshaping our understanding of how power actually functioned in early medieval Deccan. Rather than viewing Chalukya authority as a top-down system of control, scholars now recognize it as a sophisticated network of practices—woven together through temple patronage, copper-plate grants, and carefully negotiated alliances with local elites. This shift in perspective reveals that Chalukya power was not simply inherited or conquered; it was continuously constructed, performed, and reinforced through everyday administrative practices, sacred architecture, and strategic land redistribution.

The Chalukya Dynasty: Rulers of a Networked Deccan

Historical Context and Geographic Reach

The Chalukyas (6th–12th centuries CE) emerged as one of the most significant dynasties of the Deccan region, ruling vast territories that encompassed both Western and Eastern domains. The Western Chalukyas controlled areas centered around Badami and later Kalyani, while the Eastern Chalukyas dominated the Vengi region. This geographical division was not a sign of weakness but rather a sophisticated administrative strategy that allowed the dynasty to maintain influence across diverse regions with distinct cultural, linguistic, and economic characteristics.

Beyond the Model of Centralized Empire

Traditional historical narratives have often portrayed medieval Indian dynasties as centralized empires with absolute monarchs wielding power from capital cities. The Chalukya case complicates this model significantly. Rather than a unified, monolithic state structure, Deccan power under the Chalukyas operated as a network of negotiated relationships. Local elites, temple institutions, agrarian communities, and emerging feudatory chiefs all played active roles in sustaining and legitimizing Chalukya rule. This networked approach enabled the dynasty to accommodate regional diversity while maintaining broader political cohesion—a model that proved remarkably effective across six centuries of rule.

Material Evidence: The Kodad Copper Plates and Mudimanikyam Temple

The Kodad Copper Plate (c. 918 CE)

One of the most significant recent discoveries is the Kodad Copper Plate, dated to approximately 918 CE during the reign of a Vengi Chalukya king. This inscribed plate is far more than a ceremonial artifact; it represents a crucial administrative document that reveals how power was systematically documented and disseminated.[1]

The Kodad plate records a coronation grant—an official allocation of land and privileges awarded to celebrate a royal succession. The text provides several layers of historical information: a detailed genealogy of the ruling family, specifications of land rewards granted to favored nobles and institutions, and explicit taxation clauses that clarified revenue rights and obligations. By examining such documents, we gain insight into how military service was converted into permanent landed privileges—a process that formalized social hierarchy and bound regional elites to the Chalukya crown through tangible economic benefits.

Significantly, the Kodad plate contains the earliest clear reference to the emerging Kakatiya chiefs, a lineage that would eventually establish its own powerful dynasty in the region. This notation illustrates how Chalukya inscriptions served as administrative records that tracked the rise of new regional powers, a dynamic relationship rather than static dominance.

The Mudimanikyam Panchakūta Temple (8th–9th century)

While inscriptions document administrative decisions, architecture demonstrates power in physical space. The Mudimanikyam temple complex in Telangana, constructed during the 8th–9th centuries, exemplifies the distinctive Chalukya approach to sacred architecture. The temple is remarkable for its unique five-shrine configuration—a design known as panchakuta (five towers)—which represents a sophisticated synthesis of architectural traditions.

The complex blends elements of both Kadamba and Nagara architectural styles, reflecting the cosmopolitan architectural culture of the Deccan. Rather than imposing a single standardized temple design across their empire, the Chalukyas appears to have encouraged regional architectural experimentation and adaptation. This flexibility strengthened their cultural authority because temples served dual purposes: they functioned as ritual centers for religious communities and simultaneously acted as tangible markers of royal presence and patronage. A Chalukya temple was not merely a place of worship—it was a statement of political legitimacy built into the landscape.

Expanding the Archaeological Picture: Brick Temples and New Discoveries

Brick Temple Foundations in Maharashtra (11th century)

Archaeological excavations in Maharashtra have uncovered the foundations of Chalukya-period temples constructed from brick rather than stone. This discovery, perhaps seemingly mundane, fundamentally challenges assumptions about Chalukya temple architecture. Historians had previously assumed that all significant Chalukya religious structures were built from stone, implying a uniform, monumental approach. The brick temples reveal a different reality: regional architectural experimentation and adaptation were deliberate policies, not exceptions.

The presence of diverse construction materials—stone for major complexes, brick for regional temples—suggests that Chalukya elites understood different building strategies for different contexts. Grand stone temples in Telangana and Karnataka communicated royal magnificence and permanence; more modest brick temples in Maharashtra demonstrated accessibility and cultural engagement with local communities. Together, these varied architectural strategies reinforced Chalukya authority across diverse populations and geographies.

New Copper Plate Grants from Telangana

Recently conserved copper plate grants from Telangana provide extraordinarily detailed records of agrarian administration and fiscal management. These plates record boundary descriptions with precision, specify tax divisions among different categories of land, and detail village allocations and their redistributions. Unlike the Kodad plate, which focuses on royal coronation, these records illuminate the administrative machinery of everyday governance.

These documents reveal a sophisticated understanding of land as a political instrument. Grants of land were not merely economic transactions; they were calculated acts of resource redistribution designed to secure and maintain the loyalty of local elites. Each plate can be read as evidence of deliberate fiscal policy intended to balance competing interests and consolidate authority. As the presentation notes, “land is equal to the currency of political negotiation” in the Chalukya context—a profound insight into the material basis of medieval power.

Methodology: How Scholars Reconstruct the Past

Understanding Chalukya power requires a multidisciplinary approach that synthesizes diverse types of evidence. Scholars examining this period employ several complementary research techniques:

Epigraphic Analysis: Scholars carefully translate and analyze copper plates and stone inscriptions, extracting genealogical information, administrative details, and references to contemporary personalities and places. This linguistic detective work reveals how ruling families represented themselves and legitimized their authority through written language.

Architectural Study: Detailed examination of temple plans, stylistic elements, construction techniques, and spatial organization provides evidence of aesthetic choices, regional influences, and the pragmatic concerns of builders. Architecture speaks when documents are silent.

Prosopography: This technique involves systematically tracking named individuals mentioned in inscriptions—nobles, officials, priests, and merchants—across multiple documents. By tracing individuals through space and time, scholars reconstruct networks of power and patronage that connected royal courts to regional societies.

Archaeological Context: Careful excavation, material analysis, and scientific dating techniques (such as radiocarbon analysis) ground inscriptions and architecture in chronological frameworks and material reality.

Synthesis: The final step integrates all this evidence. When copper plate texts are cross-linked with temple foundations, genealogical references with architectural styles, and administrative records with excavation reports, a fuller picture emerges—one that shows how Chalukya authority was constructed through ritual performance, economic distribution, and everyday administrative practice rather than brute force alone.

Rewriting Chalukya History: From Royal Chronicles to Institutional Practice

The Institutional Turn

Recent discoveries fundamentally alter how we conceptualize Chalukya rule. Rather than reading chronicles of royal conquest and succession, scholars now focus on the everyday institutions that sustained power: the bureaucratic systems that recorded grants, the temple organizations that managed resources, the elite networks that mediated between royal authority and local communities, and the agricultural base that generated the surplus wealth necessary to support courts, temples, armies, and administration.

This shift from “top-down” models of power to “institutional” models represents one of the most significant methodological changes in medieval Indian historiography. It acknowledges that power operates through systems and relationships, not merely through the decisions of individual rulers.

The Kodad Plates and Legal Transformation

The Kodad plates exemplify this institutional approach. These documents reveal how military service could be converted into permanent landed privileges through legal text and bureaucratic procedure. A warrior rewarded by a Chalukya king received not merely a temporary gift but a heritable right—a foundation for dynasty-building at the regional level. Over generations, such grants accumulated and transformed military subordinates into quasi-independent feudatory chiefs. This process, documented in the Kodad plates and similar inscriptions, explains how large empires gradually fragmented into smaller principalities while maintaining the ideology of a unified system.

Temple Building as Political Strategy

The Mudimanikyam and brick temple discoveries demonstrate that both monumental and modest temple construction were deliberate political strategies. Temples were not merely expressions of religious piety; they were tools for projecting political and cultural presence into territories where royal courts might be geographically distant. A well-constructed, beautifully designed temple in a regional town served as a permanent advertisement of royal patronage and cultural sophistication.

Agrarian Administration and Elite Loyalty

The newly conserved copper plate grants from Telangana provide the most granular evidence for how Chalukya power was maintained through agrarian management. These plates record:

- Boundary specifications: Precise definitions of land parcels, indicating sophisticated cartographic understanding

- Tax divisions: Categories of land taxed at different rates, reflecting different agricultural potentials and uses

- Village allocations: Systematic distribution of resources among communities and individuals

These records illuminate a political economy where land grants were carefully calibrated to reward loyal subordinates while maintaining agricultural productivity. An elite family granted fertile river-valley land would prosper and remain grateful; a family granted marginal lands might seek alliance elsewhere. The grants thus represent calculated political decisions, not arbitrary donations. Each plate is a small window into the pragmatic calculations of medieval power.

Conclusion: Toward a More Complete Understanding

The discovery and analysis of Kodad copper plates, Mudimanikyam temple, brick temple foundations, and newly conserved Telangana grants collectively reshape our understanding of the Chalukya dynasty. These material remains demonstrate that Chalukya power was not the product of centralized royal authority imposing itself from above. Rather, it emerged from a sophisticated web of interconnected practices: inscriptions that documented decisions and fixed them in public memory, temples that physically manifested royal piety and authority, land grants that bound regional elites through economic self-interest, and administrative networks that coordinated diverse territories.

The Kodad plates show how legal texts formalized the conversion of military service into hereditary privilege, thereby enabling the gradual emergence of regional feudatory dynasties. The Mudimanikyam temple complex and brick temple foundations demonstrate that Chalukya elites deliberately employed architecture—whether monumental or modest—to express political presence and engage with diverse communities across their vast territories.

Most importantly, these discoveries shift scholarly focus from courtly chronicles and royal conquests to the everyday institutions that sustained Chalukya rule: the scribes who wrote grants, the priests who consecrated temples, the administrators who managed villages, and the elites who negotiated power within a system of mutual obligation and benefit.

Future research in archives, excavation of additional temple sites, and scientific analysis of material remains will continue to illuminate these institutional foundations of medieval power. Yet already, these recent discoveries make clear that understanding the Chalukyas requires attending not to military campaigns alone but to the mundane instruments—stones, seals, and grants—through which authority was actually constructed and maintained across six centuries of rule in the medieval Deccan.

References

[1] Kodad Copper Plate (c. 918 CE). Records coronation grant of Vengi Chalukya king with genealogy, land rewards, and taxation clauses. Earliest clear reference to emerging Kakatiya chiefs.

Further Reading

- Mudimanikyam Panchakūta Temple (8th–9th century). Five-shrine Chalukya-style complex in Telangana with architectural blend of Kadamba and Nagara traditions.

- Brick Temple Foundations (11th century, Maharashtra). Archaeological evidence of regional architectural adaptation and experimentation.

- Copper Plate Grants (Telangana). Records of agrarian administration, tax divisions, and village allocations demonstrating detailed fiscal management strategies.

articles

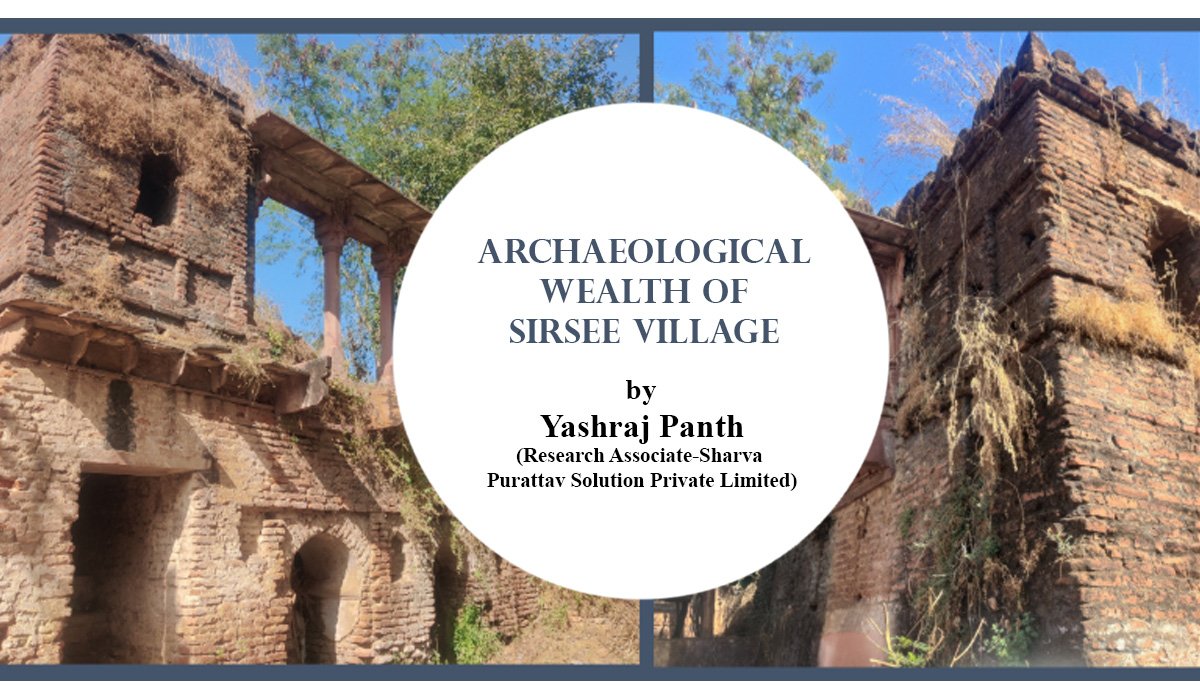

Archaeological Wealth of Sirsee Village

Published

7 days agoon

January 13, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

Sirsee Village in Lalitpur district, Uttar Pradesh, reveals a treasure trove of archaeological remains spanning centuries. This small settlement, rich in sculptures, hero stones, temple fragments, and a moated fort, connects to broader historical networks of the Gupta, Gurjara-Pratihara, and Bundela periods. Recent documentation highlights its untapped potential for understanding regional cultural continuity.

Location and Context

Sirsee lies 28 km from Lalitpur, 54 km from Deogarh, 10 km from Siron Khurd (ancient Siyadoni), and 24 km from Talbehat. Nestled amid key historical centers from the Gupta (4th-6th century CE) and post-Gupta eras, it sits near trade routes like the Jhansi-Bhopal path. Nearby Siyadoni, founded in the Gurjara-Pratihara period (8th-11th century CE), underscores Sirsee’s role in economic and cultural exchanges.

Archaeological Sites

Researchers identified seven key locations with artifacts, many in deteriorated states yet revered by locals.

Site 1: Features a hero stone and temple members, hinting at martial commemorations and religious structures.

Site 2: Includes a fort with Surya and Ganesha sculptures, Bundela-style jharokha (balcony), and a temple complex encircled by a moat.

Site 3: Hosts a Mahishasur Mardini (Durga slaying the buffalo demon) sculpture and mural paintings.

Site 4: Contains broken sculptures, an inscription, hero-stone fragments, and a Hanuman figure near temple ruins.

Site 5: Displays additional broken sculptures and ruins, possibly linked to later shrines.

Site 6: Encompasses another temple complex with structural remnants.

Site 7 (implied): Sati stambha (memorial pillars) and further fragments, indicating post-medieval practices.

Satellite imagery from Google Earth (2025 Airbus and Maxar) maps these sites, showing the fort’s scale (up to 200m) and strategic layout.

Key Artifacts

Sculptures dominate, including broken icons of deities like Mahishasur Mardini, Surya, Ganesha, and Hanuman, often in black stone or similar material. Hero stones and sati stambhas suggest battles and sati rituals, common in medieval India. Inscriptions, though fragmented, may reveal patronage or events, while temple fragments point to Shaivite or Vaishnavite worship. Bundela-style elements, like jharokhas, link to 16th-18th century Rajput architecture in Bundelkhand.

Historical Significance

Earliest occupation likely dates to the 11th-12th century CE, based on sculptural styles, though proximity to Gupta sites suggests earlier influences. The fort implies defensive needs, possibly tied to trade route conflicts or regional power struggles. Hero stones evoke battles, aligning with Pratihara-era warfare, while the moat and location near Siyadoni indicate a trade or worship hub. Continuity persists as villagers worship these relics, blending ancient heritage with living tradition.

Research Questions

The presentation raises critical queries: What defines Sirsee’s occupation timeline? Why build a fort here? Did trade or pilgrimage drive its prominence? Evidence of wars? Connections to Gupta, Pratihara, or Bundela rulers? No systematic study exists, urging documentation to trace settlement origins and evolution. Yashraj Panth, Research Associate at Sharva Purattav Solution Private Limited, calls for further exploration.

Sirsee embodies Bundelkhand’s layered past, from medieval sculptures to Bundela forts, demanding preservation and study.

UNDERSTANDING THE CHRONOLOGY OF RAIGADH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE GIVEN TO ITS STRUCTURAL MONUMENTS

IHAR Member Presents Research at 2nd International Conference on Guru Padmasambhava, Odisha

Stones, Seals & Grants: Reweaving Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Archaeological Wealth of Sirsee Village

Unveiling Ancient Footprints: Archaeological Discovery in the Khairi-Bhandan River Basin of Odisha

Bharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

Bringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

Panel Discussion on Sati

Bengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

Panel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution

Debugging the wrong historical narratives – Vedveery Arya – Exclusive podcast

The Untold History Of Ancient India – A Scientific Narration

Some new evidence in Veda Shakhas about their Epoch by Shri Mrugendra Vinod ji

West Bengal’s textbooks must reflect true heritage – Sahana Singh at webinar ‘Vision Bengal’

Bringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

Trending

-

Events2 years ago

Events2 years agoBharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

-

Videos3 years ago

Videos3 years agoBringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

-

Videos11 years ago

Videos11 years agoPanel Discussion on Sati

-

Events10 months ago

Events10 months agoBengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

-

Events8 months ago

Events8 months agoPanel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution