Jitendra Tiwari is a committed educator and cultural practitioner devoted to the service of Bharat through the revival and application of its eternal civilizational wisdom. His work consciously integrates education, heritage conservation, and sustainable rural development, aiming to harmonize tradition with meaningful service to society.

He served for five years as Headmaster at Govardhan Gurukul, Govardhan Eco Village, where he was deeply involved in value-based education, character formation, and community development initiatives. At present, he teaches Mathematics and English at a Gurukul in Parmanand Ashram, Prayagraj. His teaching journey—spanning Prayagraj and earlier experience in Mumbai—has strengthened his resolve to nurture disciplined, holistic learning among students, shaping them into responsible future leaders of society and the nation.

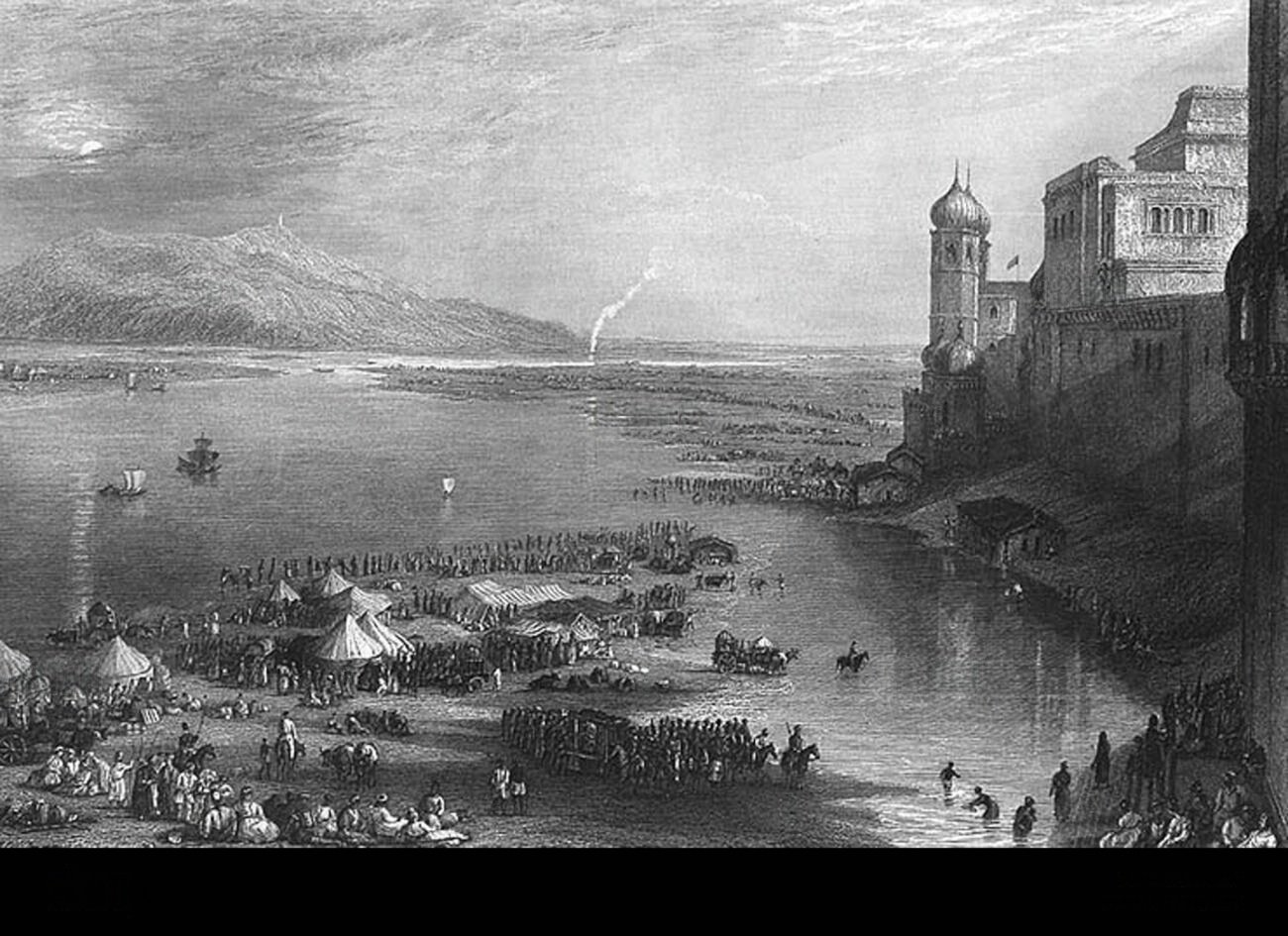

Through the Sri Adishankaracharya Foundation, he actively works to promote Panchgavya-based organic farming, cow protection, farmer and artisan empowerment, and digital documentation of Bharat’s rich heritage. He also curates heritage walks in Prayagraj and develops educational modules and guidebooks grounded in the region’s sacred history and cultural legacy.

Deeply inspired by the teachings of great Acharyas—especially Jagadguru Shankaracharya Swami Nishchalanand Saraswati Maharaj—Jitendra Tiwari views his life’s work as a humble offering toward the protection, propagation, and lived practice of Bharat’s cultural and spiritual heritage.

Events2 years ago

Events2 years ago

Videos3 years ago

Videos3 years ago

Events11 months ago

Events11 months ago

Videos11 years ago

Videos11 years ago

Events10 months ago

Events10 months ago