articles

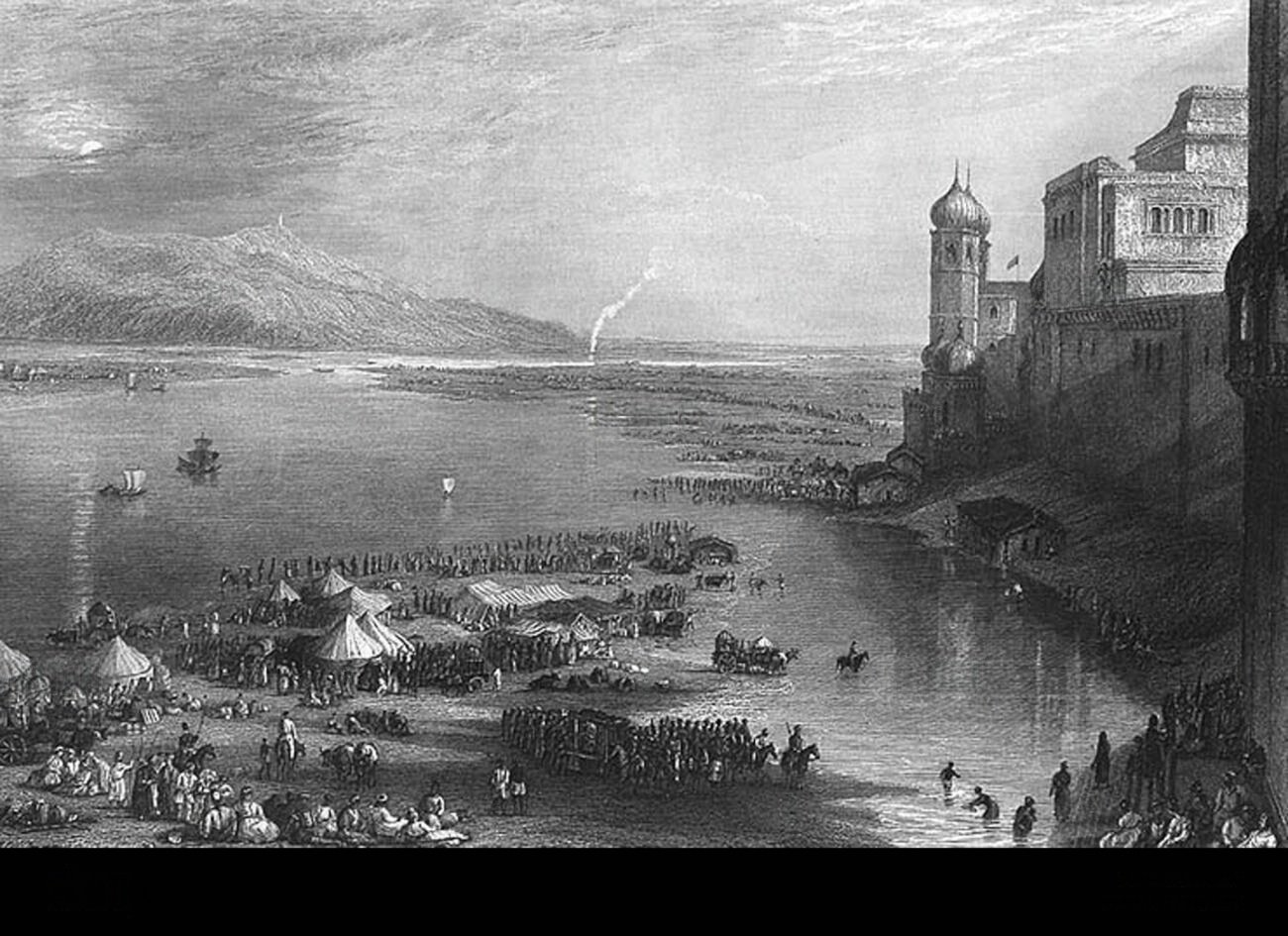

John Mildenhall and the Early English Presence in Mughal India: A Perspective

-

Events2 years ago

Events2 years agoBharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

-

Videos3 years ago

Videos3 years agoBringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

-

Events11 months ago

Events11 months agoBengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

-

Videos11 years ago

Videos11 years agoPanel Discussion on Sati

-

Events9 months ago

Events9 months agoPanel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution