articles

FAMINES during British Rule

Published

6 years agoon

By

ihar

Author: Dr. Jayakumar Srinivasan

Press Release: https://www.esamskriti.com/e/History/Indian-History/Famines-During-British-Rule-1.aspx

More than 50 million died in famines during British rule, yet many school text books do not mention about them, or say thousands died. Read all about the famines.

To read the same article in Tamil please click on PDF.

Our team was asked by a State Government SCERT Textbook Board to review 6 to 8 standard Social Sciences textbook. We made many recommendations for change of content. The State adopted about half of those suggestions. Let us look at one example.

In the context of the Zamindari system, take a look at the following extract from the 8th standard textbook 1

It is true that the British policies ruined our agricultural system. But let us draw our attention to the sentence “There were great famines which killed thousands of people”.

A famine is a situation where there is an extreme scarcity of food, especially grains. Many of us many not have had a first hand-experience of a famine because the last famine was in 1943. However, much research has been done on the study of famines in India, especially during the colonial period.

In an important book Late Victorian Holocausts 2, summarized by Fred Magdoff 3, Mike Davis mentions that there were 17 famines in the 2,000 years before British rule. In comparison, in the 120 years of British rule, there were 31 serious famines. Davis argues that the seeds of underdevelopment in what later became known as the Third World were sown in this era of High Imperialism, as the price for capitalist modernization was paid in the currency of millions of peasants’ lives. This fact should impel us to understand the British role in creating intense famines in India.

Here is a list of some major famines during British rule in India. 4

| Year | Name | Region | Deaths | Comment |

| 1769–70 | Great Bengal Famine | Bihar, Northern and Central Bengal | 10 Million | About one third of the then population of Bengal |

| 1783–84 | Chalisa famine | Delhi,UP, Punjab,Rajasthan, Kashmir | 11 Million | Severe famine. Large areas were depopulated. |

| 1791–92 | Doji bara famineorSkull famine | Hyderabad,Central India,Deccan,Gujarat, Southern Rajasthan | 11 Million | One of the most severe famines known. People died in such numbers that they could not be cremated or buried. |

| 1860–61 | Upper Doab | Rajasthan | 2 Million | |

| 1865-67 | Orissa famine | Bihar, Orissa, Parts of Southern India | 1 Million | The British Secretary of State for India, Lord Salisbury, did nothing for two months, by which time a million people had died |

| 1868–70 | Rajputana famine | Rajasthan | 1.5 Million | |

| 1876–78 | Great Madras Famine | Mysore and Hyderabad States (Madras Presidency) | 6-10 Mil | |

| 1896–97 | Indian famine | Rajasthan, parts of Central India and Hyderabad | 5 Million | |

| 1943–44 | Bengal famine | Bengal | 3.6 Million | 1.5 from starvation; 2.1 from epidemics. |

In an 1883 Volume on Rural Bengal 5, W. Hunter gives a vivid and disturbing picture of the 1770 Bengal Famine, “All through the stifling summer of 1770 the people went on dying. The husbandmen sold their cattle; they sold their implements of agriculture; they devoured their seed-grain; they sold their sons and daughters, till … no buyer of children could be found; they ate the leaves of trees and the grass of the field; and in June, 1770, the Resident at the Durbar affirmed that the living were feeding on the dead.

Day and night a torrent of famished and disease-stricken wretches poured into the great cities. …pestilence had broken out. … we find small-pox at Moorshedabad, … The streets were blocked up with … heaps of the dying and dead. … even the dogs and jackals, the public scavengers of the East, became unable to accomplish their revolting work, and the multitude of mangled and festering corpses at length threatened the existence of the citizens.

Starving and shelter less crowds crawled despairingly from one deserted village to another in a vain search for food, or a resting-place in which to hide themselves from the rain. The epidemics incident to the season were thus spread over the whole country; … Millions of famished wretches died in the struggle to live … their last gaze being probably fixed on the densely-covered fields that would ripen only a little too late for them…”

About a quarter to a third of the population of Bengal starved to death in about a ten-month period. In 1865–66, severe drought struck Odisha and was met by British official inaction.

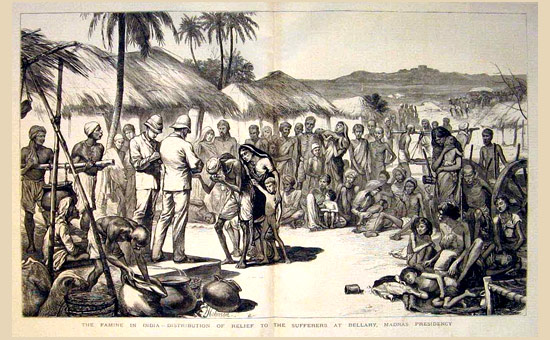

Victims pictured in 1877 Reference 4.

Victims pictured in 1877 Reference 4.

Relief Distribution in Bellary Reference 4. Great Famine 1876 to 78.

Relief Distribution in Bellary Reference 4. Great Famine 1876 to 78.

An important work to understand the role of British during the period 1939-45 (World War II), is Madhusree Mukerjee’s book “Churchill’s Secret War” 6 where she shows that the 20th Century’s greatest hero is also its greatest villain.

When asked to release more grain to India, Churchill said “I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits.” When the Delhi Government sent a telegram to him painting a picture of the horrible devastation and the number of people who had died, his only response was, “Then why hasn’t (Mahatma) Gandhi died yet?”

How to imagine the scale of loss?

The Gaja cyclone of Tamil Nadu in November 2018, which devastated the livelihoods of 500,000 families by leveling coconut, cashew and mango farms killed about 40 people. The 2004 Tsunami killed 230,000 across 14 countries.

The number of Indians who died in famines in Colonial India is 50 million. The scale of loss is incomparable.

What can India do now?

Indian school textbooks should bring out British brutality unambiguously, as these were facts of our history. In the absence of critique of the colonial period, students can come away with the false notion that colonization was the best thing that happened to India.

After our team sent this critique to the State, the Editorial Board replaced one word “thousands” by the word ‘millions” 1. While this is welcome, the text makes it appear that the British rule was benevolent to India. That view needs to be refuted and completely restated that the British were disinterested in the welfare of India!

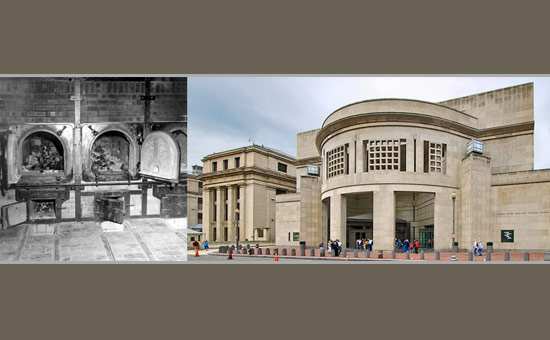

We can also learn from the West. For example, to memorialize the Jewish Holocaust (where close to 6 Million Jews were deliberately killed in Europe during 1941-45), the US has a museum – called the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. In addition, almost every child going to school in this world likely learns about the Holocaust.

The infamous Gas Chambers of the Nazi Holocaust Ref 8n Holocaust Museum USA Ref 9.

The infamous Gas Chambers of the Nazi Holocaust Ref 8n Holocaust Museum USA Ref 9.

India should establish monuments in West Bengal and other places to memorialize this genocide that killed as many people as the World War I (40 Million), and World War II (60 Million).

What were factors contributing to an increased incidence and severity of famines during the British rule of India? We will review this in a future article.

References

1. Social Studies, Class VIII, Hyderabad: SCERT, Telangana, 2018.

2. M. Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, Verso Books, 2017.

3. F. Magdoff, “Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. By Mike Davis 2001. Verso, London and New York,” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, vol. 20, pp. 190-192, 2007.

4. “Timelines of Major Famines in India during British Rule.” (Online).

5. W. W. Hunter, “Annals Of Rural Bengal,” vol. 1, 1883.

6. M. Mukerjee, Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India during World War II, India Penguin, 2018.

7.”Bengal famine of 1943″. To read Bengal famine and Responsibility for Holocaust

8. G. Will, “A showcase of the vilest and noblest manifestations of humanity,” 26 April 2018.

You may like

articles

UNDERSTANDING THE CHRONOLOGY OF RAIGADH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE GIVEN TO ITS STRUCTURAL MONUMENTS

Published

4 days agoon

January 16, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

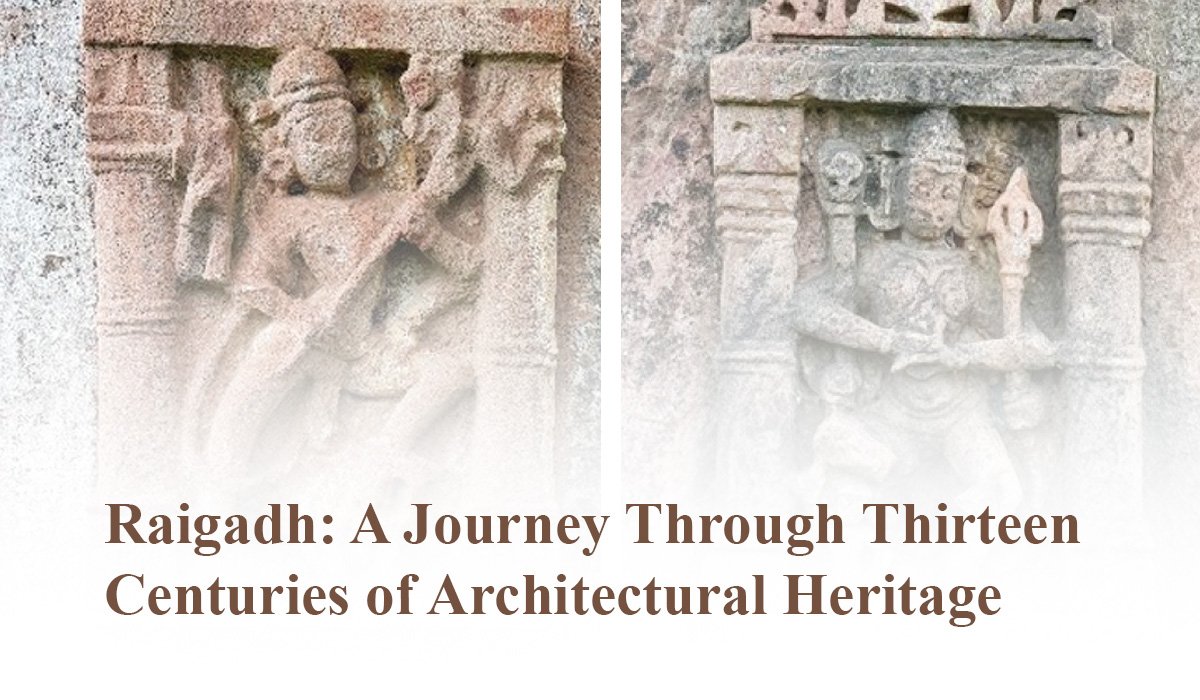

Raigadh: A Journey Through Thirteen Centuries of Architectural Heritage

Nestled in the Sabarkantha district of Gujarat, the small village of Raigadh (23°36’17” N, 73°10’42” E) stands as a remarkable open-air museum of Indian architectural evolution. From the late 7th century to the 20th century, this humble settlement has accumulated an extraordinary collection of structural monuments that chronicle the reign of multiple dynasties and the transformation of religious beliefs and practices. By studying Raigadh’s monuments, we can trace the architectural innovations, iconographical changes, and cultural shifts that shaped North Gujarat’s history.

The Maitraka Legacy: The Mota Mahadev Temple

The oldest surviving monument in Raigadh is the Mota Mahadev temple, dating to the late 7th century CE during the Maitraka period. This Shiva temple exemplifies the Phamsana architectural style, featuring a distinctive Ksoni or Gandharic-type Shikhara (spire). The original Maitraka design consisted of a Shikhara and a Garbhagriha (inner sanctum), adorned with intricate sculptures of Ganesha and Maithuna (amorous couple) figures that reveal the artistic sophistication of this ancient dynasty. What makes this temple particularly significant is its continuous religious importance. Centuries later, during the Solanki period (10th century), the temple underwent substantial renovations. The Solanki additions included a Mandapa (entrance hall) with a Kakshasana (bench-like structure), complete with plain pillars topped with lotus patterns. This evolution reveals how temples were actively modified across generations, adapting to changing worship practices. The temple boasts sculptures from both periods, including a standing Ganesha from the Maitraka era and later additions like a Nandi (bull mount of Shiva), Pranala (water channel), and a goddess figure, likely Parvati. Though the temple has undergone modern renovations with lime mortar and cement, it remains a living temple, worshipped especially during auspicious occasions like Mahashivaratri.

The Saindhava Contribution: Kashi Vishwanath Temple

The 9th century witnessed the construction of the Kashi Vishwanath temple during the Saindhava period, reflecting the dynasty’s influence in North Gujarat. Built entirely in sandstone, this temple showcases a Phamsana Vimana with a Ksoni Phamsanakara Shikhara—a pyramidal or diamond-shaped design that distinguishes it from contemporary structures. The east-facing temple follows an architectural plan featuring a Vimana with a sanctum and no ambulatory path, representing a distinct approach to temple design. The sculptural program of this temple deserves particular attention. The northern wall displays Andhakasuravedha, a four-handed form of Shiva depicted with a trident and the demon Andhakasura positioned above. The western wall features Bhairavi, the feminine counterpart of Bhairava, captured in an energetic Rudra Tandava (cosmic dance) with bent legs and an attending drummer. The southern wall houses Chamunda, a form of Katyayni and one of the Sapta Matrika (Seven Mothers), rendered in surprisingly human form rather than skeletal. These sculptures reveal sophisticated iconographical knowledge and demonstrate the 9th-century artistic tradition’s depth. Currently, the temple survives as a living sanctuary, though its sculptures show weathering, and structural elements like pillars and amlaka (stone finial) display signs of decay. It remains an active worship site on significant Hindu festivals, preserving unbroken continuity of devotion spanning over a millennium.

Innovation and Utility: The Solanki Stepwells

Contemporary with the Kashi Vishwanath temple’s later phases, the 10th-century Solanki period produced remarkable stepwells (Bhadra) that reflect advanced hydraulic engineering. These structures, constructed in sandstone with an east-west orientation, descend six storeys deep, featuring curved arches on each level. One stepwell includes a small chamber at its terminus, adorned with a Ganesha sculpture on its lintel, connecting utilitarian architecture with spiritual significance. The third storey houses a Chamunda sculpture whose stylistic qualities echo the iconographical changes occurring in this period. These stepwells appear strategically positioned near the Kashi Vishwanath temple, suggesting integrated temple complexes designed for both religious and practical purposes. The architectural features, particularly the pillar designs, parallel those found in the Solanki Mandapa of Mota Mahadev, indicating consistent construction methodologies across different monument types.

The Jain Testament: The Solanki Jain Temple

Built during the 11th or 12th century under Solanki patronage—likely under monarchs like Jayasimha Siddharaja or Kumarapal—the Jain temple dedicated to Sri Kunthunath (the seventeenth Jain Tirthankara) represents significant architectural complexity. The temple follows a comprehensive architectural plan including a Vimana, Garbhagriha, multiple Mandapas, and an Antrala (intermediate chamber). Sculptures of Sri Kunthunath and Vardhaman Mahavira adorn its walls, while a Vyali (mythical creature) appears on the lintel. Two inscriptions, written in Devanagari script, provide invaluable documentary evidence. The first, dated to Samvata 1717, records donations by Bhavanidas and his ancestors. The second mentions Lakha, identified as the sculptor of the Sri Kunthunath figure. These inscriptions document religious practices and preserve the names of patron families, offering rare glimpses into medieval Gujarati society. Despite its architectural sophistication, the temple currently stands in a ruined state, a poignant reminder of cultural heritage’s fragility.

Later Developments: Medieval and Modern Monuments

Subsequent centuries added new layers to Raigadh’s architectural narrative. The 14th-15th century Shakti temple, locally known as Repri Mata temple, reflects the Maru-Gurjara architectural style. The 17th-18th century Chhatri (cenotaph), dedicated to rulers of the Marwar dynasty governing Idar, stands on the village’s southern foothills in ruined condition. Most recently, the Goswami community, arriving in the early 20th century, established over 50 Samadhis (memorial structures), of which 28 remain today, representing modern funerary architecture and spiritual continuity.

Conclusion:

Reading History in Stone Raigadh’s monuments form an extraordinary chronological narrative spanning thirteen centuries. From the Maitraka Shiva temple to 20th-century Samadhis, these structures document the rise and fall of dynasties, the evolution of religious iconography, the permanence of worship, and the persistence of community memory. By preserving Raigadh’s architectural heritage, we conserve not merely buildings, but the lived history of Gujarat’s diverse populations and their enduring cultural values.

articles

Stones, Seals & Grants: Reweaving Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Published

4 days agoon

January 16, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

Stones, Seals & Grants: Understanding Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Introduction

For centuries, the Chalukya dynasty has been studied through the lens of royal conquest and centralized empires. However, recent archaeological and epigraphic discoveries are fundamentally reshaping our understanding of how power actually functioned in early medieval Deccan. Rather than viewing Chalukya authority as a top-down system of control, scholars now recognize it as a sophisticated network of practices—woven together through temple patronage, copper-plate grants, and carefully negotiated alliances with local elites. This shift in perspective reveals that Chalukya power was not simply inherited or conquered; it was continuously constructed, performed, and reinforced through everyday administrative practices, sacred architecture, and strategic land redistribution.

The Chalukya Dynasty: Rulers of a Networked Deccan

Historical Context and Geographic Reach

The Chalukyas (6th–12th centuries CE) emerged as one of the most significant dynasties of the Deccan region, ruling vast territories that encompassed both Western and Eastern domains. The Western Chalukyas controlled areas centered around Badami and later Kalyani, while the Eastern Chalukyas dominated the Vengi region. This geographical division was not a sign of weakness but rather a sophisticated administrative strategy that allowed the dynasty to maintain influence across diverse regions with distinct cultural, linguistic, and economic characteristics.

Beyond the Model of Centralized Empire

Traditional historical narratives have often portrayed medieval Indian dynasties as centralized empires with absolute monarchs wielding power from capital cities. The Chalukya case complicates this model significantly. Rather than a unified, monolithic state structure, Deccan power under the Chalukyas operated as a network of negotiated relationships. Local elites, temple institutions, agrarian communities, and emerging feudatory chiefs all played active roles in sustaining and legitimizing Chalukya rule. This networked approach enabled the dynasty to accommodate regional diversity while maintaining broader political cohesion—a model that proved remarkably effective across six centuries of rule.

Material Evidence: The Kodad Copper Plates and Mudimanikyam Temple

The Kodad Copper Plate (c. 918 CE)

One of the most significant recent discoveries is the Kodad Copper Plate, dated to approximately 918 CE during the reign of a Vengi Chalukya king. This inscribed plate is far more than a ceremonial artifact; it represents a crucial administrative document that reveals how power was systematically documented and disseminated.[1]

The Kodad plate records a coronation grant—an official allocation of land and privileges awarded to celebrate a royal succession. The text provides several layers of historical information: a detailed genealogy of the ruling family, specifications of land rewards granted to favored nobles and institutions, and explicit taxation clauses that clarified revenue rights and obligations. By examining such documents, we gain insight into how military service was converted into permanent landed privileges—a process that formalized social hierarchy and bound regional elites to the Chalukya crown through tangible economic benefits.

Significantly, the Kodad plate contains the earliest clear reference to the emerging Kakatiya chiefs, a lineage that would eventually establish its own powerful dynasty in the region. This notation illustrates how Chalukya inscriptions served as administrative records that tracked the rise of new regional powers, a dynamic relationship rather than static dominance.

The Mudimanikyam Panchakūta Temple (8th–9th century)

While inscriptions document administrative decisions, architecture demonstrates power in physical space. The Mudimanikyam temple complex in Telangana, constructed during the 8th–9th centuries, exemplifies the distinctive Chalukya approach to sacred architecture. The temple is remarkable for its unique five-shrine configuration—a design known as panchakuta (five towers)—which represents a sophisticated synthesis of architectural traditions.

The complex blends elements of both Kadamba and Nagara architectural styles, reflecting the cosmopolitan architectural culture of the Deccan. Rather than imposing a single standardized temple design across their empire, the Chalukyas appears to have encouraged regional architectural experimentation and adaptation. This flexibility strengthened their cultural authority because temples served dual purposes: they functioned as ritual centers for religious communities and simultaneously acted as tangible markers of royal presence and patronage. A Chalukya temple was not merely a place of worship—it was a statement of political legitimacy built into the landscape.

Expanding the Archaeological Picture: Brick Temples and New Discoveries

Brick Temple Foundations in Maharashtra (11th century)

Archaeological excavations in Maharashtra have uncovered the foundations of Chalukya-period temples constructed from brick rather than stone. This discovery, perhaps seemingly mundane, fundamentally challenges assumptions about Chalukya temple architecture. Historians had previously assumed that all significant Chalukya religious structures were built from stone, implying a uniform, monumental approach. The brick temples reveal a different reality: regional architectural experimentation and adaptation were deliberate policies, not exceptions.

The presence of diverse construction materials—stone for major complexes, brick for regional temples—suggests that Chalukya elites understood different building strategies for different contexts. Grand stone temples in Telangana and Karnataka communicated royal magnificence and permanence; more modest brick temples in Maharashtra demonstrated accessibility and cultural engagement with local communities. Together, these varied architectural strategies reinforced Chalukya authority across diverse populations and geographies.

New Copper Plate Grants from Telangana

Recently conserved copper plate grants from Telangana provide extraordinarily detailed records of agrarian administration and fiscal management. These plates record boundary descriptions with precision, specify tax divisions among different categories of land, and detail village allocations and their redistributions. Unlike the Kodad plate, which focuses on royal coronation, these records illuminate the administrative machinery of everyday governance.

These documents reveal a sophisticated understanding of land as a political instrument. Grants of land were not merely economic transactions; they were calculated acts of resource redistribution designed to secure and maintain the loyalty of local elites. Each plate can be read as evidence of deliberate fiscal policy intended to balance competing interests and consolidate authority. As the presentation notes, “land is equal to the currency of political negotiation” in the Chalukya context—a profound insight into the material basis of medieval power.

Methodology: How Scholars Reconstruct the Past

Understanding Chalukya power requires a multidisciplinary approach that synthesizes diverse types of evidence. Scholars examining this period employ several complementary research techniques:

Epigraphic Analysis: Scholars carefully translate and analyze copper plates and stone inscriptions, extracting genealogical information, administrative details, and references to contemporary personalities and places. This linguistic detective work reveals how ruling families represented themselves and legitimized their authority through written language.

Architectural Study: Detailed examination of temple plans, stylistic elements, construction techniques, and spatial organization provides evidence of aesthetic choices, regional influences, and the pragmatic concerns of builders. Architecture speaks when documents are silent.

Prosopography: This technique involves systematically tracking named individuals mentioned in inscriptions—nobles, officials, priests, and merchants—across multiple documents. By tracing individuals through space and time, scholars reconstruct networks of power and patronage that connected royal courts to regional societies.

Archaeological Context: Careful excavation, material analysis, and scientific dating techniques (such as radiocarbon analysis) ground inscriptions and architecture in chronological frameworks and material reality.

Synthesis: The final step integrates all this evidence. When copper plate texts are cross-linked with temple foundations, genealogical references with architectural styles, and administrative records with excavation reports, a fuller picture emerges—one that shows how Chalukya authority was constructed through ritual performance, economic distribution, and everyday administrative practice rather than brute force alone.

Rewriting Chalukya History: From Royal Chronicles to Institutional Practice

The Institutional Turn

Recent discoveries fundamentally alter how we conceptualize Chalukya rule. Rather than reading chronicles of royal conquest and succession, scholars now focus on the everyday institutions that sustained power: the bureaucratic systems that recorded grants, the temple organizations that managed resources, the elite networks that mediated between royal authority and local communities, and the agricultural base that generated the surplus wealth necessary to support courts, temples, armies, and administration.

This shift from “top-down” models of power to “institutional” models represents one of the most significant methodological changes in medieval Indian historiography. It acknowledges that power operates through systems and relationships, not merely through the decisions of individual rulers.

The Kodad Plates and Legal Transformation

The Kodad plates exemplify this institutional approach. These documents reveal how military service could be converted into permanent landed privileges through legal text and bureaucratic procedure. A warrior rewarded by a Chalukya king received not merely a temporary gift but a heritable right—a foundation for dynasty-building at the regional level. Over generations, such grants accumulated and transformed military subordinates into quasi-independent feudatory chiefs. This process, documented in the Kodad plates and similar inscriptions, explains how large empires gradually fragmented into smaller principalities while maintaining the ideology of a unified system.

Temple Building as Political Strategy

The Mudimanikyam and brick temple discoveries demonstrate that both monumental and modest temple construction were deliberate political strategies. Temples were not merely expressions of religious piety; they were tools for projecting political and cultural presence into territories where royal courts might be geographically distant. A well-constructed, beautifully designed temple in a regional town served as a permanent advertisement of royal patronage and cultural sophistication.

Agrarian Administration and Elite Loyalty

The newly conserved copper plate grants from Telangana provide the most granular evidence for how Chalukya power was maintained through agrarian management. These plates record:

- Boundary specifications: Precise definitions of land parcels, indicating sophisticated cartographic understanding

- Tax divisions: Categories of land taxed at different rates, reflecting different agricultural potentials and uses

- Village allocations: Systematic distribution of resources among communities and individuals

These records illuminate a political economy where land grants were carefully calibrated to reward loyal subordinates while maintaining agricultural productivity. An elite family granted fertile river-valley land would prosper and remain grateful; a family granted marginal lands might seek alliance elsewhere. The grants thus represent calculated political decisions, not arbitrary donations. Each plate is a small window into the pragmatic calculations of medieval power.

Conclusion: Toward a More Complete Understanding

The discovery and analysis of Kodad copper plates, Mudimanikyam temple, brick temple foundations, and newly conserved Telangana grants collectively reshape our understanding of the Chalukya dynasty. These material remains demonstrate that Chalukya power was not the product of centralized royal authority imposing itself from above. Rather, it emerged from a sophisticated web of interconnected practices: inscriptions that documented decisions and fixed them in public memory, temples that physically manifested royal piety and authority, land grants that bound regional elites through economic self-interest, and administrative networks that coordinated diverse territories.

The Kodad plates show how legal texts formalized the conversion of military service into hereditary privilege, thereby enabling the gradual emergence of regional feudatory dynasties. The Mudimanikyam temple complex and brick temple foundations demonstrate that Chalukya elites deliberately employed architecture—whether monumental or modest—to express political presence and engage with diverse communities across their vast territories.

Most importantly, these discoveries shift scholarly focus from courtly chronicles and royal conquests to the everyday institutions that sustained Chalukya rule: the scribes who wrote grants, the priests who consecrated temples, the administrators who managed villages, and the elites who negotiated power within a system of mutual obligation and benefit.

Future research in archives, excavation of additional temple sites, and scientific analysis of material remains will continue to illuminate these institutional foundations of medieval power. Yet already, these recent discoveries make clear that understanding the Chalukyas requires attending not to military campaigns alone but to the mundane instruments—stones, seals, and grants—through which authority was actually constructed and maintained across six centuries of rule in the medieval Deccan.

References

[1] Kodad Copper Plate (c. 918 CE). Records coronation grant of Vengi Chalukya king with genealogy, land rewards, and taxation clauses. Earliest clear reference to emerging Kakatiya chiefs.

Further Reading

- Mudimanikyam Panchakūta Temple (8th–9th century). Five-shrine Chalukya-style complex in Telangana with architectural blend of Kadamba and Nagara traditions.

- Brick Temple Foundations (11th century, Maharashtra). Archaeological evidence of regional architectural adaptation and experimentation.

- Copper Plate Grants (Telangana). Records of agrarian administration, tax divisions, and village allocations demonstrating detailed fiscal management strategies.

articles

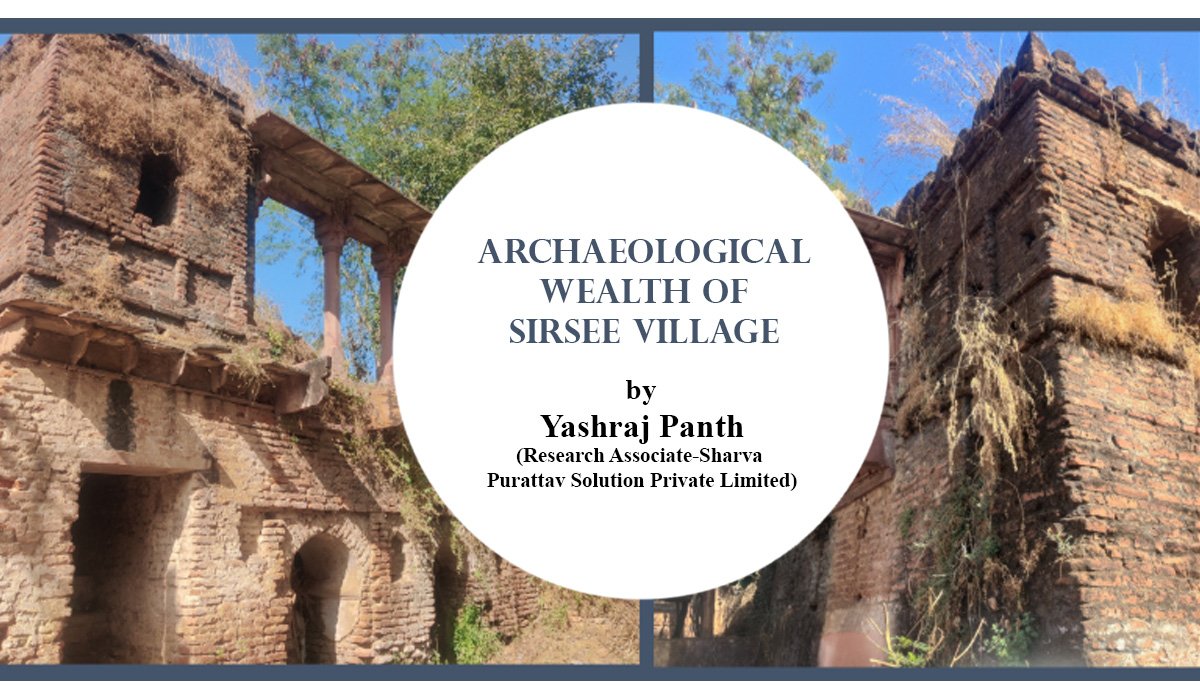

Archaeological Wealth of Sirsee Village

Published

7 days agoon

January 13, 2026By

Suprabho Roy

Sirsee Village in Lalitpur district, Uttar Pradesh, reveals a treasure trove of archaeological remains spanning centuries. This small settlement, rich in sculptures, hero stones, temple fragments, and a moated fort, connects to broader historical networks of the Gupta, Gurjara-Pratihara, and Bundela periods. Recent documentation highlights its untapped potential for understanding regional cultural continuity.

Location and Context

Sirsee lies 28 km from Lalitpur, 54 km from Deogarh, 10 km from Siron Khurd (ancient Siyadoni), and 24 km from Talbehat. Nestled amid key historical centers from the Gupta (4th-6th century CE) and post-Gupta eras, it sits near trade routes like the Jhansi-Bhopal path. Nearby Siyadoni, founded in the Gurjara-Pratihara period (8th-11th century CE), underscores Sirsee’s role in economic and cultural exchanges.

Archaeological Sites

Researchers identified seven key locations with artifacts, many in deteriorated states yet revered by locals.

Site 1: Features a hero stone and temple members, hinting at martial commemorations and religious structures.

Site 2: Includes a fort with Surya and Ganesha sculptures, Bundela-style jharokha (balcony), and a temple complex encircled by a moat.

Site 3: Hosts a Mahishasur Mardini (Durga slaying the buffalo demon) sculpture and mural paintings.

Site 4: Contains broken sculptures, an inscription, hero-stone fragments, and a Hanuman figure near temple ruins.

Site 5: Displays additional broken sculptures and ruins, possibly linked to later shrines.

Site 6: Encompasses another temple complex with structural remnants.

Site 7 (implied): Sati stambha (memorial pillars) and further fragments, indicating post-medieval practices.

Satellite imagery from Google Earth (2025 Airbus and Maxar) maps these sites, showing the fort’s scale (up to 200m) and strategic layout.

Key Artifacts

Sculptures dominate, including broken icons of deities like Mahishasur Mardini, Surya, Ganesha, and Hanuman, often in black stone or similar material. Hero stones and sati stambhas suggest battles and sati rituals, common in medieval India. Inscriptions, though fragmented, may reveal patronage or events, while temple fragments point to Shaivite or Vaishnavite worship. Bundela-style elements, like jharokhas, link to 16th-18th century Rajput architecture in Bundelkhand.

Historical Significance

Earliest occupation likely dates to the 11th-12th century CE, based on sculptural styles, though proximity to Gupta sites suggests earlier influences. The fort implies defensive needs, possibly tied to trade route conflicts or regional power struggles. Hero stones evoke battles, aligning with Pratihara-era warfare, while the moat and location near Siyadoni indicate a trade or worship hub. Continuity persists as villagers worship these relics, blending ancient heritage with living tradition.

Research Questions

The presentation raises critical queries: What defines Sirsee’s occupation timeline? Why build a fort here? Did trade or pilgrimage drive its prominence? Evidence of wars? Connections to Gupta, Pratihara, or Bundela rulers? No systematic study exists, urging documentation to trace settlement origins and evolution. Yashraj Panth, Research Associate at Sharva Purattav Solution Private Limited, calls for further exploration.

Sirsee embodies Bundelkhand’s layered past, from medieval sculptures to Bundela forts, demanding preservation and study.

UNDERSTANDING THE CHRONOLOGY OF RAIGADH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE GIVEN TO ITS STRUCTURAL MONUMENTS

IHAR Member Presents Research at 2nd International Conference on Guru Padmasambhava, Odisha

Stones, Seals & Grants: Reweaving Chalukya Power in the Early Medieval Deccan

Archaeological Wealth of Sirsee Village

Unveiling Ancient Footprints: Archaeological Discovery in the Khairi-Bhandan River Basin of Odisha

Bharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

Bringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

Panel Discussion on Sati

Bengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

Panel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution

Debugging the wrong historical narratives – Vedveery Arya – Exclusive podcast

The Untold History Of Ancient India – A Scientific Narration

Some new evidence in Veda Shakhas about their Epoch by Shri Mrugendra Vinod ji

West Bengal’s textbooks must reflect true heritage – Sahana Singh at webinar ‘Vision Bengal’

Bringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

Trending

-

Events2 years ago

Events2 years agoBharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

-

Videos3 years ago

Videos3 years agoBringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

-

Videos11 years ago

Videos11 years agoPanel Discussion on Sati

-

Events10 months ago

Events10 months agoBengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

-

Events8 months ago

Events8 months agoPanel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution