articles

PANCHMADIYA COMPLEX: HISTORICAL NARRATIVES & ARCHAEOLOGICAL RE-EVALUATION

Published

2 months agoon

By

ihar

The Panchmadiya Temple Complex: Layers of History and Sacred Tradition

Introduction

Nestled in the heartland of Madhya Pradesh, the Panchmadiya temple complex at Singrampur stands as a silent witness to centuries of religious transformation and cultural evolution. This remarkable archaeological site, located in the eastern reaches of Madhya Pradesh, represents far more than a collection of ancient ruins—it embodies the continuous reinterpretation of sacred space across multiple civilizations and belief systems.

The Panchmadiya complex is distinguished by its unique chronological layering, where Shaiva monasticism of the Kalachuri period gave way to Vaishnavite devotion, and subsequently transformed into a site of local veneration connected to legendary figures and heroic memories. This article explores the architectural remains, sculptural treasures, and historical narratives that make this temple complex a compelling case study in Indian religious and cultural history.

Location and Geographic Significance

The Panchmadiya temple complex is situated in Singrampur, within the broader cultural landscape of eastern Madhya Pradesh. The region is surrounded by numerous other archaeological sites of considerable importance, including Kodal, Nohta, and various locations scattered across the Kalachuri heartland. The geographic placement of the complex, documented through Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) Jabalpur Circle records, places it within a network of medieval monastic and temple sites that once flourished across the region.

This strategic location in the medieval period placed the complex at the confluence of important trade and pilgrimage routes, facilitating cultural exchange and religious patronage from ruling dynasties of the era.

The Kalachuri Period: Origins as a Monastic Site (10th-12th Century CE)

Establishment and Religious Purpose

The Panchmadiya complex originated during the Kalachuri period (10th-12th century CE) as a Shaiva monastic site, or matha. The Kalachuri dynasty, which ruled much of central India during this period, were known patrons of Hindu religious institutions, particularly those dedicated to Shaiva traditions—the worship of Lord Shiva.

The architectural evidence suggests that the complex was established as a minor but significant monastic center. The term matha refers to a monastic establishment where monks would reside, study, and practice religious discipline. These institutions played crucial roles in preserving and transmitting religious knowledge, philosophical teachings, and ritual practices.

Mattamayura Matha Architecture

One of the most significant structures at the Panchmadiya complex is the Mattamayura Matha, which survives in a repurposed form known today as the Maladevi Temple. The architectural features of this structure demonstrate clear similarities to other Mattamayura Mathas constructed throughout Madhya Pradesh between the 9th and 11th centuries CE.

The interior architectural design reveals the sophisticated planning typical of monastic establishments from this period. Mattamayura Mathas, found scattered across the Kalachuri territories, were purpose-built monastic dwellings that accommodated resident monks, featuring:

- Central courtyards for communal activities

- Individual cells for resident monks

- Shrines for daily worship and meditation

- Storage areas for manuscripts and provisions

The continued existence and active worship at this site, even in its repurposed form, speaks to the enduring sanctity attributed to the location by successive communities.

The Dasabhuji Chamunda Sculpture

Within the Mattamayura Matha stands an ancient sculpture of Dasabhuji Chamunda (the ten-armed form of the goddess), which is still venerated by local devotees as Maladevi. This sculpture represents a connection to the Shaiva-Tantric traditions that were prominent during the Kalachuri period. The Dasabhuji Chamunda is an aspect of the fierce goddess tradition in Hindu theology, often associated with protection and the destruction of evil forces.

The fact that this sculpture remains in active worship, covered in vermillion and receiving daily offerings, demonstrates how ancient religious practices maintain continuity despite changing political and cultural circumstances. This represents a living link to the devotional practices of over a thousand years ago.

Architectural Components of the Complex

The Central Vishnu Shrine

During the 12th-13th centuries CE, the Panchmadiya complex underwent significant transformation with the introduction of Vaishnavite elements. The construction of a Vishnu Shrine at the center of a large platform marked this religious shift toward Vaishnavism (the worship of Lord Vishnu).

The shrine measures 4.9 meters by 2.4 meters and appears to have originally functioned as a mandapika temple—a small, autonomous shrine structure. The architectural design comprises:

- Mandapa: The pillared hall or vestibule

- Garbhagriha: The inner sanctum or womb chamber where the primary deity would be installed

The construction technique is notable: stone blocks were arranged in dry masonry (without mortar), demonstrating the building practices of medieval artisans. The lintel (the horizontal stone above the entrance) serves as the primary identifying feature of the temple’s Vaishnavite affiliation, bearing iconographic elements significant to Vishnu worship.

The Door Jamb and Iconography

A particularly valuable archaeological feature is the ornamental door jamb associated with the Vishnu shrine. Though incomplete, this architectural fragment retains almost all traditional iconographic elements of medieval temple design. The most significant identifying feature is the Tridev depiction—a representation of the Hindu trinity comprising Brahma (creator), Vishnu (preserver), and Shiva (destroyer).

Such iconographic representations on door frames and jambs served multiple purposes: they identified the temple’s religious affiliation, blessed all who entered the sanctum, and conveyed theological concepts through visual imagery. This reflected the medieval Hindu temple tradition of combining architecture with sculpture to create a comprehensive religious statement.

Subsidiary Shrines

At each of the four corners of the central platform stand the remains of subsidiary shrines, each measuring 3.8 meters by 2.9 meters. These smaller shrines likely housed different divine aspects or deity forms associated with the primary deity. Only the misraka pillars (supporting pillars) survive today, providing evidence of the once-elaborate structure.

The arrangement of these subsidiary shrines around the central Vishnu shrine follows the classical Indian temple plan, where multiple manifestations of divinity are positioned within a unified sacred geography. This organizational principle reflects deep theological concepts about the multiplicity and unity of divine forms.

Heaps of Architectural Remains

Beyond the main structures, archaeological surveys have identified significant heaps of architectural remains scattered throughout the complex, including:

- Pillar shafts of various dimensions

- Blocks of stone from collapsed structures

- Quadrangular stone beams that once supported roofing or upper floors

These architectural fragments suggest that the complex was far more elaborate in its heyday than what survives today. The accumulation of these remains indicates either deliberate demolition or gradual deterioration due to natural causes and the passage of time.

Sacred Sculptures and Spiritual Continuity

Hanuman and Shaiva Sculptures

The complex preserves very few sculptural remains compared to many other medieval temples, suggesting either that statuary was removed or destroyed in antiquity, or that the site never housed extensive sculptural programs. Among the surviving pieces are ancient sculptures of Hanuman (the devoted monkey devotee of Rama) and various Shaiva sculptures (representations connected to Shiva worship).

What is particularly remarkable is that these ancient sculptures remain in active worship, their surfaces covered in vermillion (sindur), receiving regular offerings from devoted worshippers. This continuity of worship demonstrates how even when a temple’s original function or historical narrative may be forgotten, the sacred character of the sculptures persists across generations.

Other Individual Shrines

Throughout the complex, various individual shrines have been constructed around ancient sculptures and sacred remains. These modern shrines, built of stone, represent the continued tradition of worshipping ancient sculptures at the site. They indicate how local communities have adapted and preserved the sacred character of the space, even as the original historical context receded into the past.

The Sati Stones: A Window into Medieval Society

Among the most poignant remains at the Panchmadiya complex are inscribed and uninscribed Sati stones. These memorial stones commemorate women who performed sati—the practice of widow self-immolation on their husband’s funeral pyre, traditionally understood as an act honoring a deceased warrior husband.

Historical and Social Context

The presence of Sati stones at the complex, particularly their association with the Garha Mandala period (14th-16th centuries CE) and folklore surrounding Queen Durgavati, reveals important aspects of medieval Madhya Pradesh society:

- Martial culture: The placement of Sati stones indicates the presence of warrior families and feudal nobility in the region

- Women’s agency and honor codes: While modern perspectives critique the practice, these stones represented the values and social frameworks of medieval times

- Commemoration and memory: The inscribed and uninscribed stones served to perpetuate the memory of individuals deemed heroic by their societies

The Sati stones transform the Panchmadiya complex from merely a religious site into a repository of social history, revealing the complex relationship between warfare, honor, gender, and spirituality in medieval India.

The Garha Mandala Period and Folkloric Transformation (14th-16th Century CE)

Shifting Religious and Political Landscapes

As the Kalachuri dynasty declined and the power of early medieval dynasties waned, the Panchmadiya complex underwent a fundamental transformation. The Garha Mandala period saw the rise of the Gond dynasty and later the famous Rajput warrior queen Durgavati, whose reign became legendary in regional folklore.

During this period, the site’s religious significance was reinterpreted through the lens of local heroic memory and legend. The association with Queen Durgavati, a legendary figure in Madhya Pradesh history known for her valor and resistance, gave the site new folkloric significance distinct from its earlier monastic and temple functions.

Queen Durgavati and Local Memory

Queen Durgavati has become an iconic figure in regional consciousness, representing courage, leadership, and tragic nobility. Her association with the Panchmadiya complex, whether historical or legendary, demonstrates how sacred sites become repositories for community memory and identity. The site transformed from a functioning religious institution into a place where history, heroism, and devotion merged in the collective imagination.

Chronological Layering: The Archaeological Narrative

The Panchmadiya temple complex represents a continuous chronological layering of cultural and religious identities. Rather than representing a single moment in time, it embodies multiple overlapping historical periods:

Layer One: Shaiva Monasticism (10th-12th century CE)

The foundation—a minor Kalachuri-period monastic establishment dedicated to Shaiva traditions, where monks engaged in spiritual practice and the preservation of sacred knowledge.

Layer Two: Vaishnavite Elements (12th-13th century CE)

The addition of Vaishnavite structures and sculptures, indicating a shift in patronage and religious emphasis. This was likely caused by changing dynasties, patronage patterns, or broader religious trends favoring Vaishnava devotionalism.

Layer Three: Hero Stones and Legends (14th-16th century CE)

The placement of Sati stones and the association with Queen Durgavati, transforming the site from a functioning religious institution into a memorial space commemorating martial valor and local heroism.

Layer Four: Living Worship (Present Day)

The site’s continued sacred character, demonstrated through the active worship of ancient sculptures and the operation of functioning shrines where local communities maintain religious practices.

Archaeological Significance and Broader Context

The Mattamayura Matha Network

The Panchmadiya complex’s Mattamayura Matha represents one node in a larger network of similar structures distributed across medieval Madhya Pradesh. The distribution of these mathas indicates:

- Organized monastic movements with standardized architectural plans

- A network of Shaiva institutions sharing resources, knowledge, and religious authority

- The extent of Kalachuri influence across the region during the 9th-11th centuries CE

This network perspective helps scholars understand how religious knowledge, artistic practices, and spiritual traditions were transmitted and maintained across medieval India.

Architectural Continuity and Adaptation

The site demonstrates important principles of medieval Indian architectural practice:

- Dry masonry techniques: Stone blocks arranged without mortar, allowing for flexibility in reuse and adaptation

- Modular shrine design: Individual shrines that could function independently or as components of larger complexes

- Adaptive reuse: Structures repurposed for new religious functions while maintaining their fundamental sacred character

Conservation and Living Heritage

The Panchmadiya complex represents a unique category of heritage site—one where ancient structures continue to function as active religious spaces. Unlike many archaeological sites that are preserved as historical artifacts, the Panchmadiya complex remains a site of worship, pilgrimage, and spiritual practice.

This characteristic presents both opportunities and challenges for conservation:

- Living tradition: The continued worship ensures ongoing community engagement with the site

- Risk factors: Active use can accelerate deterioration of ancient structures

- Community stewardship: Local communities’ sense of ownership and responsibility for the site enhances preservation

The involvement of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) Jabalpur Circle in documentation and research demonstrates the commitment to balancing preservation with cultural continuity.

Conclusion

The Panchmadiya temple complex at Singrampur stands as a remarkable palimpsest of Indian history, where successive civilizations have written their spiritual and cultural narratives atop earlier layers. From its origins as a Kalachuri monastic center dedicated to Shaiva traditions, through its transformation into a Vaishnavite temple complex, to its contemporary function as a site of local veneration and folk memory, the Panchmadiya complex embodies the adaptability and resilience of Indian religious traditions.

The surviving architectural elements—the Mattamayura Matha, the Vishnu shrine, the subsidiary structures, the ancient sculptures—testify to the skill of medieval artisans and the depth of religious commitment among ancient patrons and worshippers. The Sati stones provide poignant evidence of the social complexities of medieval society, while the continued worship at the site demonstrates the unbroken spiritual thread connecting the ancient past to the present.

For historians, archaeologists, and pilgrims alike, the Panchmadiya complex offers invaluable insights into the religious, architectural, and social history of medieval Madhya Pradesh. It reminds us that archaeological sites are never merely repositories of the past, but living spaces where history, spirituality, and community memory continue to intersect and evolve.

The complex invites further research, careful conservation, and respectful engagement from scholars and visitors—ensuring that the voices of ancient monks, dedicated sculptors, and faithful devotees across centuries will continue to resonate through the centuries to come.

articles

Why not Conserve? Delving into the Ground Realities of Conserving Unprotected Heritage in India

Published

3 weeks agoon

February 9, 2026By

ihar

About the Article Author - Protyoy Sen

Protyoy Sen is an architect, currently pursuing his Masters in Building Conservation at the Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University. Having graduated from CEPT University Ahmedabad in 2023, his primary interest lies in the tangible values of conserving heritage, incentivisation for its stakeholders, and aligning conservation with broader goals of urban planning and sustainability. He believes that the potential of heritage in creating a rooted economy is currently underutilised in India, and attributes his passion to the architectural legacy of his hometown, Calcutta. His earlier research delved into the practical challenges of conserving heritage buildings, and its quantifiable benefits for the society.

Protyoy also has over two years of experience in the industry, having worked with Indian heritage bodies such as INTACH and DRONAH. His work, during this time, included projects with private clients, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), and State Archaeology and Tourism departments.

articles

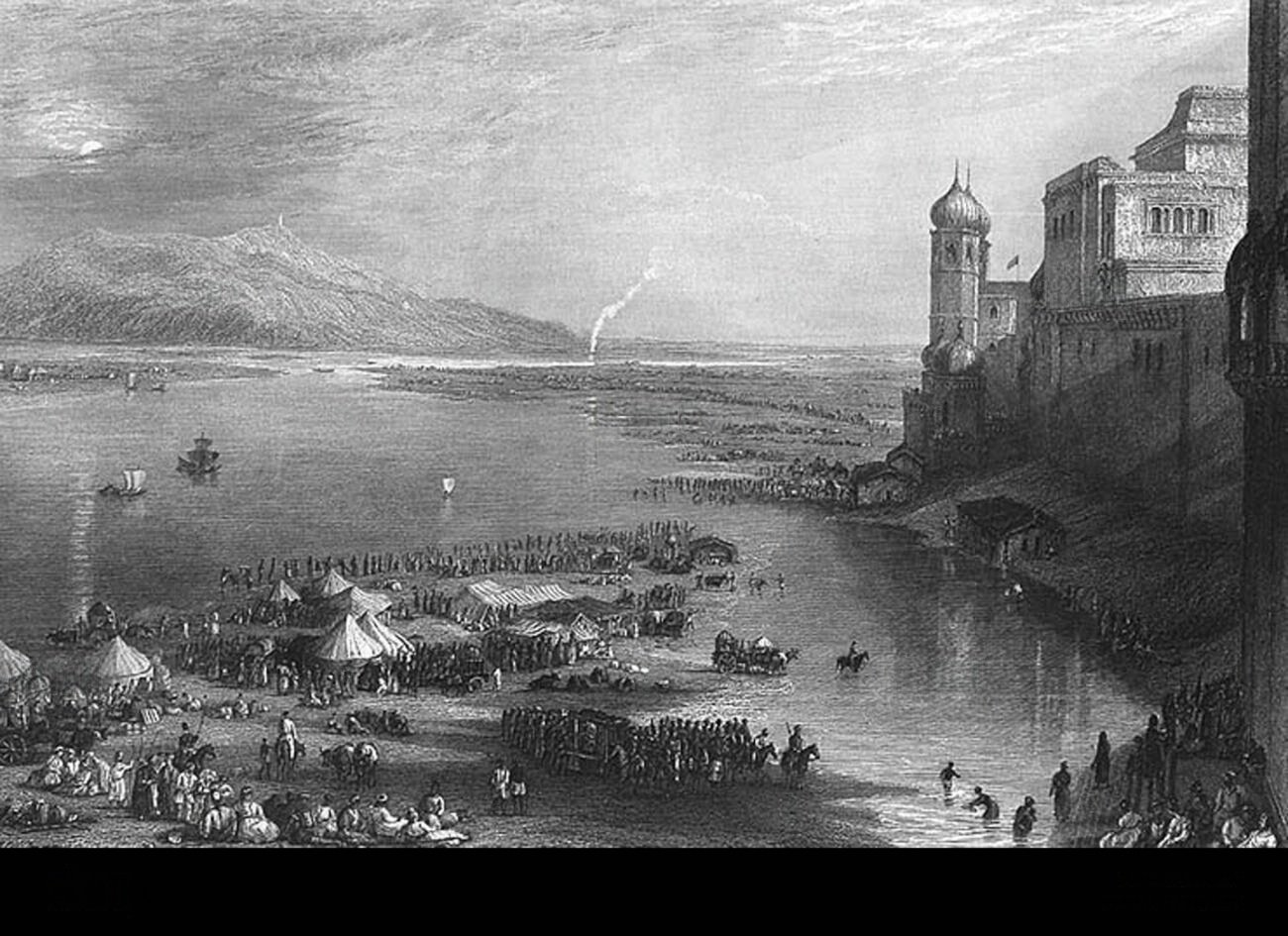

Prayagraj and Its Sacred Glory (Prayāga Māhātmya)

Published

1 month agoon

January 30, 2026By

ihar

About the Article Author - Jitendra Tiwari

Jitendra Tiwari is a committed educator and cultural practitioner devoted to the service of Bharat through the revival and application of its eternal civilizational wisdom. His work consciously integrates education, heritage conservation, and sustainable rural development, aiming to harmonize tradition with meaningful service to society.

He served for five years as Headmaster at Govardhan Gurukul, Govardhan Eco Village, where he was deeply involved in value-based education, character formation, and community development initiatives. At present, he teaches Mathematics and English at a Gurukul in Parmanand Ashram, Prayagraj. His teaching journey—spanning Prayagraj and earlier experience in Mumbai—has strengthened his resolve to nurture disciplined, holistic learning among students, shaping them into responsible future leaders of society and the nation.

Through the Sri Adishankaracharya Foundation, he actively works to promote Panchgavya-based organic farming, cow protection, farmer and artisan empowerment, and digital documentation of Bharat’s rich heritage. He also curates heritage walks in Prayagraj and develops educational modules and guidebooks grounded in the region’s sacred history and cultural legacy.

Deeply inspired by the teachings of great Acharyas—especially Jagadguru Shankaracharya Swami Nishchalanand Saraswati Maharaj—Jitendra Tiwari views his life’s work as a humble offering toward the protection, propagation, and lived practice of Bharat’s cultural and spiritual heritage.

articles

Sangam and Kumbh Mela in Bengal: The Sacred Legacy of ‘Dakshin Prayag’ Tribeni

Published

1 month agoon

January 30, 2026By

ihar

About the Article Author - Pallab Mondal

Pallab Mondal is an independent researcher and columnist with a keen interest in cultural and social issues. A committed cultural and social activist, his work focuses on engaging with society through research, writing, and grassroots perspectives. He holds an MA in Social Work from Rabindra Bharati University, which informs his analytical approach and active involvement in social and cultural discourse.

IHAR participation in Shakthi Kumbh 2026

Why not Conserve? Delving into the Ground Realities of Conserving Unprotected Heritage in India

Prayagraj and Its Sacred Glory (Prayāga Māhātmya)

Sangam and Kumbh Mela in Bengal: The Sacred Legacy of ‘Dakshin Prayag’ Tribeni

The Trail of Omkari : A Spiritual Corridor of Bangla Shaktipeeths

Bharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

Bringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

Bengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

Panel Discussion on Sati

Panel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution

Debugging the wrong historical narratives – Vedveery Arya – Exclusive podcast

The Untold History Of Ancient India – A Scientific Narration

Some new evidence in Veda Shakhas about their Epoch by Shri Mrugendra Vinod ji

West Bengal’s textbooks must reflect true heritage – Sahana Singh at webinar ‘Vision Bengal’

Bringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

Trending

-

Events2 years ago

Events2 years agoBharat Varsh – A Cradle of Civilzation – Panel Discussion

-

Videos3 years ago

Videos3 years agoBringing our Gods back home – A Conversation with Shri Vijay Kumar

-

Events11 months ago

Events11 months agoBengal’s Glorious and Diverse Heritage- Traditions and Festivals – Panel Discussion

-

Videos11 years ago

Videos11 years agoPanel Discussion on Sati

-

Events10 months ago

Events10 months agoPanel Discussion: Heritage of Firebrand Revolutionaries – Bengal The Seedbed of Revolution