Raigadh: A Journey Through Thirteen Centuries of Architectural Heritage

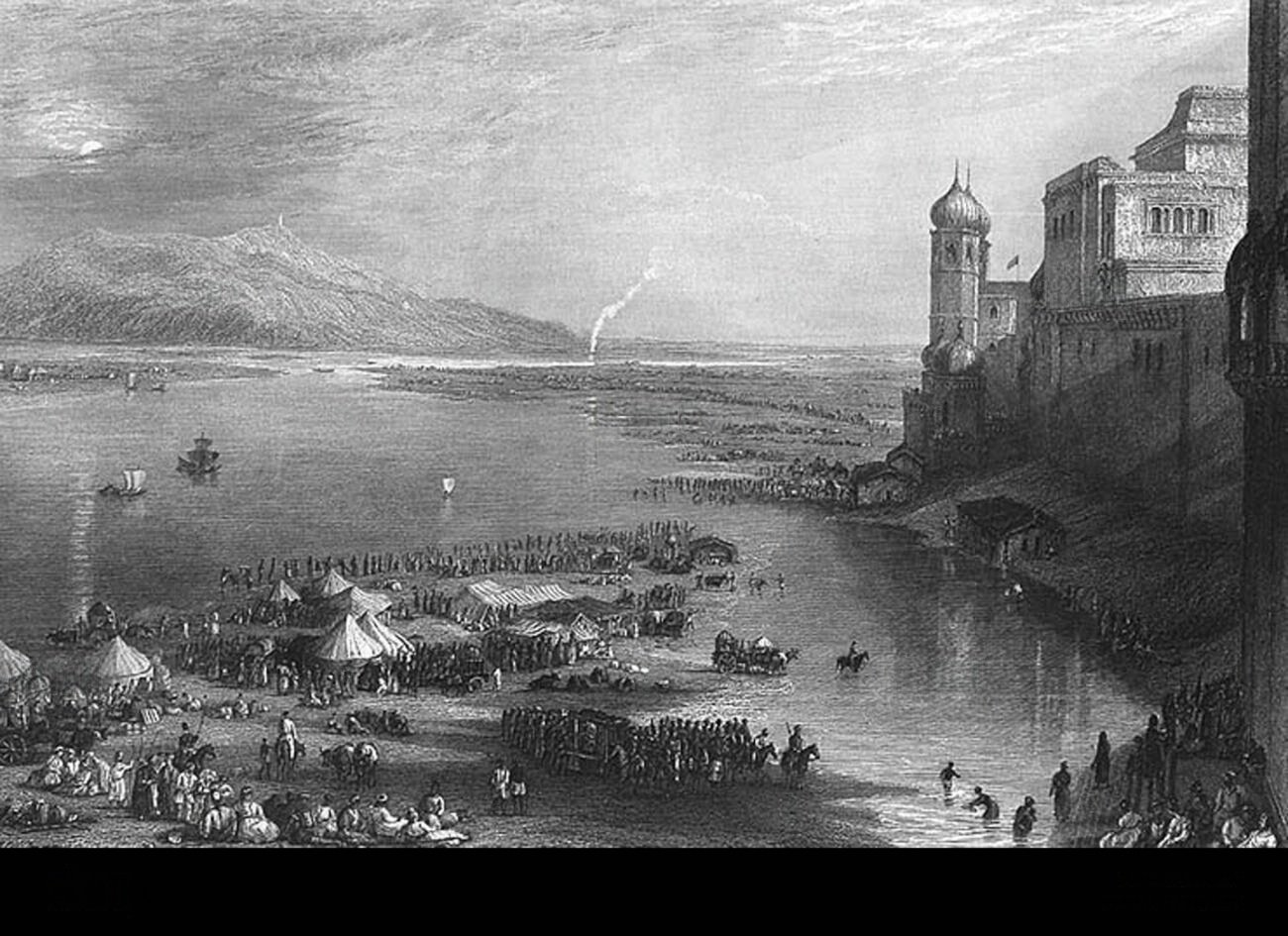

Nestled in the Sabarkantha district of Gujarat, the small village of Raigadh (23°36’17” N, 73°10’42” E) stands as a remarkable open-air museum of Indian architectural evolution. From the late 7th century to the 20th century, this humble settlement has accumulated an extraordinary collection of structural monuments that chronicle the reign of multiple dynasties and the transformation of religious beliefs and practices. By studying Raigadh’s monuments, we can trace the architectural innovations, iconographical changes, and cultural shifts that shaped North Gujarat’s history.

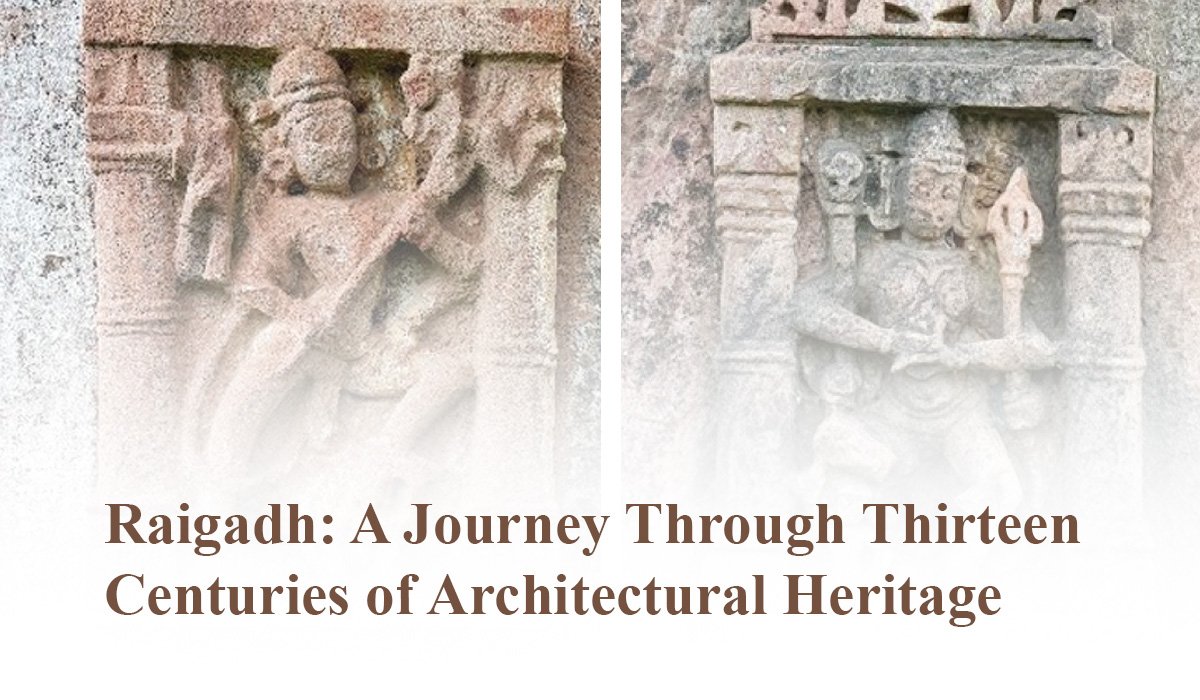

The Maitraka Legacy: The Mota Mahadev Temple

The oldest surviving monument in Raigadh is the Mota Mahadev temple, dating to the late 7th century CE during the Maitraka period. This Shiva temple exemplifies the Phamsana architectural style, featuring a distinctive Ksoni or Gandharic-type Shikhara (spire). The original Maitraka design consisted of a Shikhara and a Garbhagriha (inner sanctum), adorned with intricate sculptures of Ganesha and Maithuna (amorous couple) figures that reveal the artistic sophistication of this ancient dynasty. What makes this temple particularly significant is its continuous religious importance. Centuries later, during the Solanki period (10th century), the temple underwent substantial renovations. The Solanki additions included a Mandapa (entrance hall) with a Kakshasana (bench-like structure), complete with plain pillars topped with lotus patterns. This evolution reveals how temples were actively modified across generations, adapting to changing worship practices. The temple boasts sculptures from both periods, including a standing Ganesha from the Maitraka era and later additions like a Nandi (bull mount of Shiva), Pranala (water channel), and a goddess figure, likely Parvati. Though the temple has undergone modern renovations with lime mortar and cement, it remains a living temple, worshipped especially during auspicious occasions like Mahashivaratri.

The Saindhava Contribution: Kashi Vishwanath Temple

The 9th century witnessed the construction of the Kashi Vishwanath temple during the Saindhava period, reflecting the dynasty’s influence in North Gujarat. Built entirely in sandstone, this temple showcases a Phamsana Vimana with a Ksoni Phamsanakara Shikhara—a pyramidal or diamond-shaped design that distinguishes it from contemporary structures. The east-facing temple follows an architectural plan featuring a Vimana with a sanctum and no ambulatory path, representing a distinct approach to temple design. The sculptural program of this temple deserves particular attention. The northern wall displays Andhakasuravedha, a four-handed form of Shiva depicted with a trident and the demon Andhakasura positioned above. The western wall features Bhairavi, the feminine counterpart of Bhairava, captured in an energetic Rudra Tandava (cosmic dance) with bent legs and an attending drummer. The southern wall houses Chamunda, a form of Katyayni and one of the Sapta Matrika (Seven Mothers), rendered in surprisingly human form rather than skeletal. These sculptures reveal sophisticated iconographical knowledge and demonstrate the 9th-century artistic tradition’s depth. Currently, the temple survives as a living sanctuary, though its sculptures show weathering, and structural elements like pillars and amlaka (stone finial) display signs of decay. It remains an active worship site on significant Hindu festivals, preserving unbroken continuity of devotion spanning over a millennium.

Innovation and Utility: The Solanki Stepwells

Contemporary with the Kashi Vishwanath temple’s later phases, the 10th-century Solanki period produced remarkable stepwells (Bhadra) that reflect advanced hydraulic engineering. These structures, constructed in sandstone with an east-west orientation, descend six storeys deep, featuring curved arches on each level. One stepwell includes a small chamber at its terminus, adorned with a Ganesha sculpture on its lintel, connecting utilitarian architecture with spiritual significance. The third storey houses a Chamunda sculpture whose stylistic qualities echo the iconographical changes occurring in this period. These stepwells appear strategically positioned near the Kashi Vishwanath temple, suggesting integrated temple complexes designed for both religious and practical purposes. The architectural features, particularly the pillar designs, parallel those found in the Solanki Mandapa of Mota Mahadev, indicating consistent construction methodologies across different monument types.

The Jain Testament: The Solanki Jain Temple

Built during the 11th or 12th century under Solanki patronage—likely under monarchs like Jayasimha Siddharaja or Kumarapal—the Jain temple dedicated to Sri Kunthunath (the seventeenth Jain Tirthankara) represents significant architectural complexity. The temple follows a comprehensive architectural plan including a Vimana, Garbhagriha, multiple Mandapas, and an Antrala (intermediate chamber). Sculptures of Sri Kunthunath and Vardhaman Mahavira adorn its walls, while a Vyali (mythical creature) appears on the lintel. Two inscriptions, written in Devanagari script, provide invaluable documentary evidence. The first, dated to Samvata 1717, records donations by Bhavanidas and his ancestors. The second mentions Lakha, identified as the sculptor of the Sri Kunthunath figure. These inscriptions document religious practices and preserve the names of patron families, offering rare glimpses into medieval Gujarati society. Despite its architectural sophistication, the temple currently stands in a ruined state, a poignant reminder of cultural heritage’s fragility.

Later Developments: Medieval and Modern Monuments

Subsequent centuries added new layers to Raigadh’s architectural narrative. The 14th-15th century Shakti temple, locally known as Repri Mata temple, reflects the Maru-Gurjara architectural style. The 17th-18th century Chhatri (cenotaph), dedicated to rulers of the Marwar dynasty governing Idar, stands on the village’s southern foothills in ruined condition. Most recently, the Goswami community, arriving in the early 20th century, established over 50 Samadhis (memorial structures), of which 28 remain today, representing modern funerary architecture and spiritual continuity.

Conclusion:

Reading History in Stone Raigadh’s monuments form an extraordinary chronological narrative spanning thirteen centuries. From the Maitraka Shiva temple to 20th-century Samadhis, these structures document the rise and fall of dynasties, the evolution of religious iconography, the permanence of worship, and the persistence of community memory. By preserving Raigadh’s architectural heritage, we conserve not merely buildings, but the lived history of Gujarat’s diverse populations and their enduring cultural values.

Events2 years ago

Events2 years ago

Videos3 years ago

Videos3 years ago

Events11 months ago

Events11 months ago

Videos11 years ago

Videos11 years ago

Events10 months ago

Events10 months ago